1938

From that moment on the whole country was in fear. Preparations started for the arrival of the German troops, and it took only one day and they were in Vienna. There appeared flags with swastikas in almost all windows, enormous ones. SA men in brown uniforms and SS men in black uniforms marched through the streets with music bands, and enormous numbers of applauding and shouting onlookers filled the sidewalks. The enthusiasm and happiness of the Viennese was great. People who did not know each other embraced and kissed each other. Of course, great many were unhappy and stayed at home. But the others were in the majority and went out and showed their excitement and happiness.

The great German novelist Carl Zuckmayer has written such a good description of what happened in these days in Vienna, that I am tempted to bring here a few parts of that book, whose title is Als waers ein Stueck von mir (A Piece of Myself). I am quoting from the English version of that book:

That night hell broke loose. The underworld opened its gates and vomited forth the lowest, filthiest, most horrible demons it contained. The city was transformed into a nightmare painting by Hieronymus Bosch; phantoms and devils seemed to have crawled out of sewers and swamps. The air was filled with an incessant screeching, horrible, piercing, hysterical cries from the throats of men and women who continued screaming day and night. People’s faces vanished, were replaced by contorted masks; some of fear, some of cunning, some of wild, hate-filled triumph. In the course of my life I had seen something of untrammeled human instincts, of horror or panic. I had taken part in a dozen battles in the First World War, had experienced barrages, gassing, going over the top. I had witnessed the turmoil of the postwar era, the crushing of uprisings, street battles, meeting hall brawls. I was present among the bystanders during the Hitler Putsch of 1923 in Munich. I saw the early period of Nazi rule in Berlin. But none of this was comparable to those days in Vienna. What was unleashed upon Vienna had nothing to do with the seizure of power in Germany, which proceeded under the guise of legality and was met by parts of the population with alienation, skepticism, or an unsuspecting anti-nationalistic idealism, What was unleashed upon Vienna was a torrent of envy, jealousy, bitterness, blind, malignant craving for revenge. All better instincts were silenced. Probably revolution will always be horrible; but the horror may be borne, understood, assimilated, when it has sprung from genuine need, is conceived, out of conviction and true intelligence, if what has brought matters to the boiling point is a true spiritual flame. But here only the torpid masses had been unchained. Their blind destructiveness and hatred were directed against everything that nature or intelligence had refined. It was witches’ Sabbath of the mob. All that makes for human dignity was buried…

That evening we took a cab through the city, for we were planning to meet in an apartment with others in the same predicament and discuss the situation. Horch was a man of nervous temperament anyhow, and today his whole body was shaking and he was constantly repressing tears. It was no pleasure to ride through Vienna in a cab at this time. The streets were so jammed with shouting and gesticulating crowds that we could scarcely move. In the square near the opera we became stuck in the mob. Tough louts, typical rowdies, pressed against the cab windows, and stared banefully inside. Already they suspected every cab of containing a fugitive or a “bloodsucker.” “Riding a cab—must be Polish Jews. Get ’em out—beat ’em up.” While my friend almost threw up from sheer terror, I rolled down the window, abruptly thrust my arm stiffly through it almost into the men’s faces, and shouted something that sounded like “Heitler,” putting on the sharp Prussian accent of an army sergeant. I had already realized that this was the only effective feint. And so we finally reached the apartment. There a small woeful group had gathered, almost all of them people who within the hour had seen the foundation of their lives knocked out from under them. How often, in exile, have I witnessed such scenes: brooding, despairing people blown together by an evil wind and sitting like victims of a shipwreck on a sinking vessel or a reef. Oedon von Horvath was there, as well as Franz Theodor Gzokor and our Friend Albrecht Joseph. Alexander Lernet-Holenia had come also; although he himself was not directly threatened, he felt he belonged with us. Very soon a kind of gallows humor came to the fore. We were concerned with the question of saving our lives, but being together for the last time this way we felt obliged to rise above the situation with a modicum of wit. When we parted, we all felt that it was forever. Yet almost all the friends who met that evening would see each other again later on.

Several of my friends departed that same night. They were the wiser ones, for the frontiers were not effectively closed for several days. I did not want to go. Perhaps I was suffering from a kind of paralysis, of defiance or shame such reactions may well be a form of nervous shock. In any case, I told my wife that I did not intend to go abroad. “I’m not getting into any refugee train,” I said. I talked the wildest nonsense. I had a right to my native land, I said I hadn’t “done anything.” (Apparently I repressed the things I had done, my Berlin speech against Goebbels and my membership in the Iron Front, the opposition to the Nazis.) I hadn’t “committed any crime” that would justify persecution. Yet, by then, justice had vanished from Germany and persecution was raging blindly, barbarously, though under the cloak of “order and discipline.” There was no safety in having done nothing against the tyrants; one’s crime was in not having joined up with them. Quite aside from political or racial principles, anyone was liable to persecution. For the moment they decided you were different, you were an outlaw which meant being exposed to a kind of annihilation far worse than death. The fear by which dictatorships keep their subjects in check is by no means the fear of death. A person who opposes the revolutionaries in a time of upheaval must count of being killed, and to my mind that is not the worse that can happen if you feel that all human decency and dignity is going to the dogs all around you. But to be shattered physically and spiritually, to be trampled under, crushed, crippled by humiliation and torture, and still have to go on living as a slave, without identity, condemned to continuing life in its most painful and hopeless form, with no end in view and no prospect of rescue, only to die at last more miserably than an animal in the slaughterhouse that was the real horror that awaited us under the new regime. I mention all this for those who have not experienced those times or else—and this, too, seems to happen—no longer remember what it was like. What it was like surpassed the limit of imagination for the inhabitants of other countries at the time, especially the Western democracies. At this moment of confusion it also surpassed the limits of my own imagination, although I knew enough about it…

I chose these lines of Zuckmayer’s book, because almost all of that what he said applied also to me. I was in exactly the same situation as he, but the difference was that he could leave and he left a few days later and I could not, as I had a family and could not simply run away, He had no children and his wife was safe, followed him later.

When the German troops arrived the next day, enormous masses filled the streets, growing from hour to hour, shouting and singing. It was a picture never seen before in Vienna. But the anxiety and unhappiness of the Jewish people grew. Vienna, a city of 2 million people, had a large Jewish community. All together, Austria had about 200,000 Jews. We knew what had happened to the Jews in Germany, since the Nazis had taken over in 1933. We knew that they gradually had lost their positions, their possessions by confiscation, and their rights and freedom. We knew of concentration camps, of killings, and there was no end to horror stories.

It did not take long and all these things started in Vienna. There were arrests left and right, first of important people in high positions, then of rich people, but soon also of others. People who looked Jewish were arrested in the streets and were never seen again. One of the first things that happened was that people were taken out of the houses with pails of water and brushes and ordered to scrape off the red paint on the sidewalks. These were the anti-Nazi slogans, which were painted with large letters before the Germans came. It was hard to remove the paint. They brought only Jews to do that work, mostly very old people and women, and they had to kneel down and scrape the paint off with little knives and tooth brushes, while groups of people stood around, laughing and shouting.

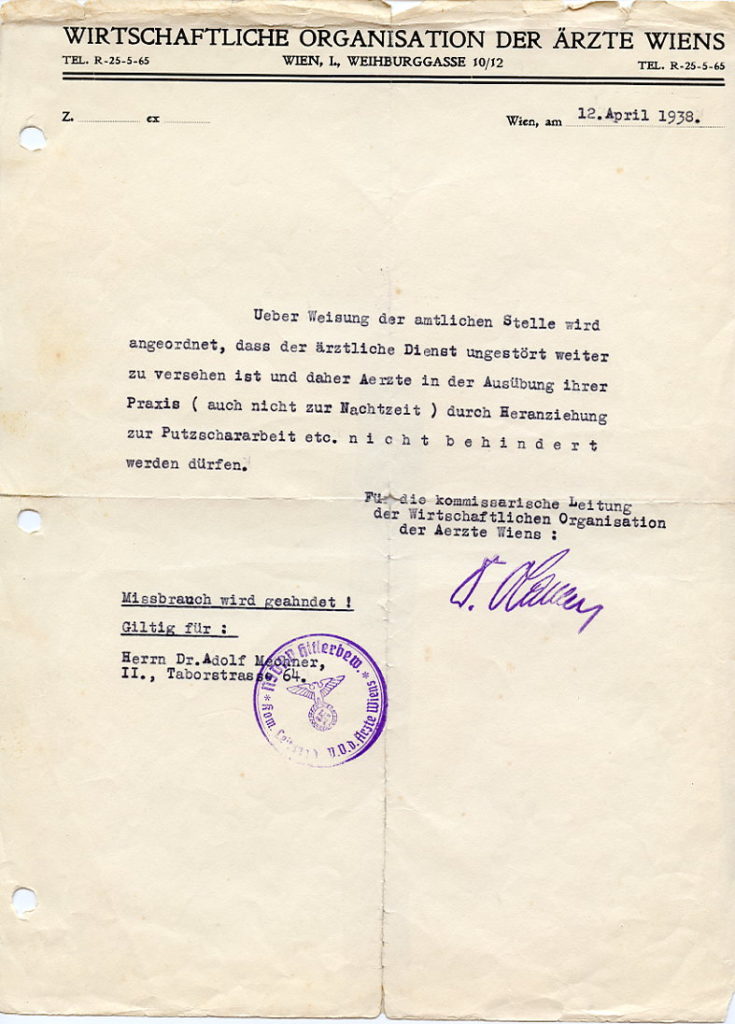

They also came to our house to take me, two young fellows in black uniforms, SS men, about 18 years old, and asked me to go with them. I resisted. I told them that as a former Frontkaempfer, which means one who had fought in the First World War for Austria, on the side of Germany, I was exempted from that kind of work. Also that it was proclaimed over the radio that doctors should not be called for such work. They said that they had not heard of it and I asked them to call up their commando to find out about it and offered them the telephone. They looked in the telephone directory, but could not find the number, and finally they gave up and left. That was a hard moment for me and my people.

In the meantime, the excitement in the city rose from hour to hour, from day to day. Near our house was a large railway station, the Nordwestbahnhof, not in use for years, and the large train area there was converted into an enormous hall for gatherings, decorated with red and black flags with swastikas. On the second or third day after the arrival of the troops, Fieldmarshal Goering visited Vienna and the preparations for his arrival were enormous. More flags, larger ones, and enormous masses of people in the streets. He passed through the street where we lived, standing in an open car, to the Nordwestbahnhof, where he spoke to the masses, asking them to join the ranks of the progress, telling them that everybody will be accepted. About the Jews he said: “Sie muessen ‘raus,” which means that they have to leave. And he added: “And they will want to leave.” Two days later Goebbels came, again riding in an open car through our street to the Nordwestbahnhof to speak to the masses. And then Hitler came. The flags had to be larger and they dug deep holes in the sidewalks and erected enormous beams, the kind we had never seen before. The day before, leaflets were strewn in the streets which said. “Hitler alive to Vienna, back dead to Berlin.” They must have been afraid now, as they put police with machine guns on the roofs of every house along the route. Jews were not allowed to look out of the windows and we had to admit to all our windows people who were needed to applaud, and we had to stay in the other rooms, which had no front windows. To prevent an attack the route after the meeting was changed and Hitler left with his entourage through other streets.

We were sitting near the radio for hours, trying to find out how the world, how the big powers reacted to the events in Austria. There were many who expected that there would be war and that our troubles would soon be over. Many thought that the whole thing would be over in a few months, that the Nazis would have difficulties to reign in Austria. Many people could leave right in the beginning and were able to escape to Italy or Switzerland. But soon the borders of Austria were tightly closed and nobody could leave anymore. We did not hear on the radio the news we expected. The so-called big powers did not do anything. We read foreign newspapers from Switzerland and France, anxious to read what was going on in the world. We found out that nothing was done, that the big powers had written off Austria.

More and more bad news arrived daily, about arrests, about pilfering of stores belonging to Jews, which we could see across the street from our windows, about simple confiscation’s and taking over of large and small businesses by people who were before employees. Then started the deportations to concentration camps in mass transports. The brother of one of our friends, Dr. Lindenfeld, was arrested in the street and deported to Dachau. Two days later, the family received a note that he had died and that an urn with his ashes could be picked up in Munich. The father of that young man refused to go there. Such stories reached us daily and many, many people decided to leave the country.

Many left illegally without passports or any documents. Some were successful in crossing the border into France or Belgium. But many were caught and sent back. Some were sent back from Switzerland, even after having reached Zurich or any other city. The consulates of all the countries in the world refused to give visas to Jews. It sounds incredible, but that was the situation at that time. One had to have a passport in the first place and to get one was enormously difficult. There were long lines at the passport offices. One had to get first a paper that he did not owe any taxes to the government, a separate paper that one did owe any taxes for owning a dog. That alone took weeks, and with a passport one had to stand in line at the consulate.

For the U.S.A. one had to have an affidavit, and people had to get up at 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning to have a chance to get into the consulate. There was a chance that one could have been arrested by the Nazis while standing in line. Visas for Switzerland, France, England, Belgium, Holland were almost impossible to obtain. One had to have somebody in these countries who could intervene there, which took months.

It was obvious that we would have to leave also. I was sitting at night at the typewriter and wrote to friends in Australia and to Dr. Hansi Hilkowicz in New York. In Australia I knew a man whom I had once met in Vienna, and he was also my patient for a little while. His name was Mr. Star. I got from him very soon an answer that he was willing to get a certificate for us. But I found out that I could not work there as a doctor, that I would have to study about 3 years at a university and then take examinations. So, I gave up on that. Prom the United States I got soon a promise from cousin Hansi, and there came soon afterwards an excellent affidavit. I took the affidavit to the American consulate and got an appointment with a consul. He asked me many questions and when I told him that I was born in Czernowitz, which was then in Rumania, he told me that I had very poor chances of getting a visa. I had not known anything about the quota system, had not known that having been born in Rumania, I would have to wait a few years to get the visa. Hedy and the children could get it, but not I.

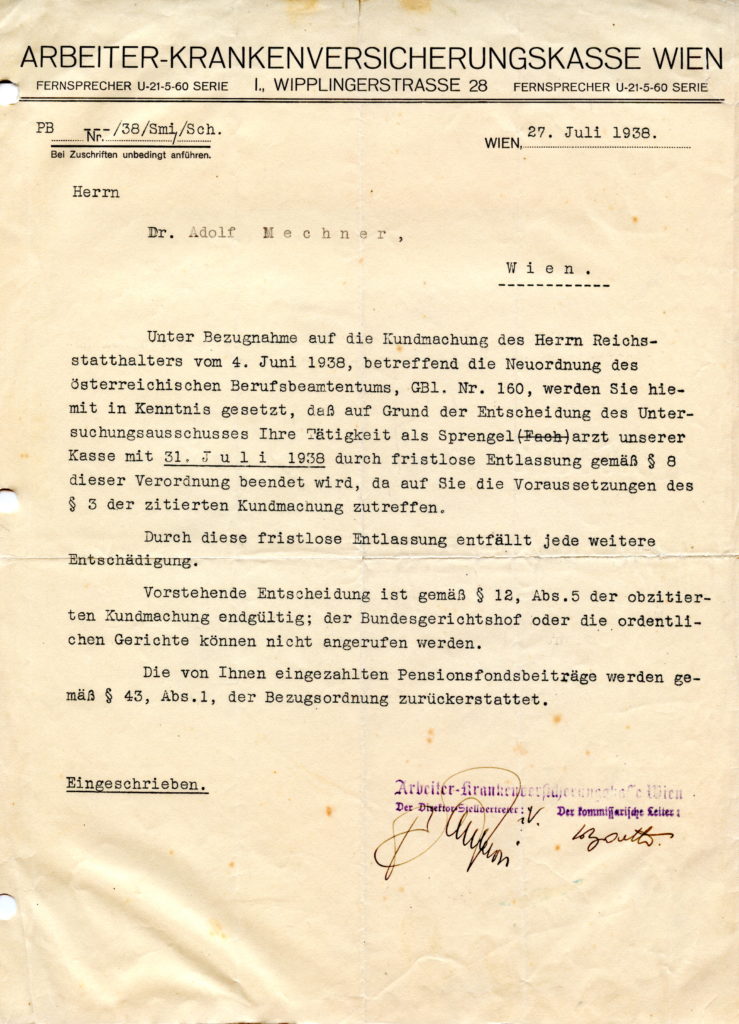

We were in a terrible dilemma. It was hard enough to decide that we should leave the country, leave everything behind. I had a flourishing practice for over nine years. My waiting room was filled with patients every day from one to five in the afternoon, and some days, when I counted the patients, there were 60 and even 75 patients, including house calls. We had a beautiful home. To give up all that was a hard decision. And there were the relatives, our beloved parents, and the others whom we would have to leave behind. Of course they wanted us to go, to be safe, no matter where, and besides us there were Lisa and Erich, who had to be saved. Lisa could get a visa for France, which our cousins Suzanne and Raymond could procure. She left in May. I will never forget the scene when she left by taxi, and her parents stood and looked, both terribly excited, as if they knew that they would never see her again. How Erich got out of the country—a long and fascinating story—will be told later by Lisl. But we were in a difficult situation and had no place to go. I had a friend, a Mr. Lackenbacher, who got a visa for himself and his wife for Haiti. I thought he was lucky. Some people went to Mauritius. Some girls went as housemaids to England, but in general every country was closed for Jews.