1938

But we had luck too. One day, I met a colleague, a lady doctor, in the street. She told me that she had heard that one can get a permit for Cuba easily. One had to deposit $500 per person and that was all that was required.

It sounded incredible, but I found out that it was true. I had no money in a foreign country. I had taken out all of it years back. But I was lucky again. An uncle of Hedy’s, Dr. Josef Feingold, came to our rescue from Paris. He was the father of John and Erich Forster. How he got to Paris is quite an interesting story. He had always lived in Vienna. One day, about 3 months after the Nazis had occupied Austria, he found in his basement 2 paintings, which he had bought many years ago. When he looked closer at them, he found that they were signed by Adolph Hitler. Hitler’s profession years back was hanging wallpapers. He also painted postcards with watercolors, which he sold in coffee houses, going from table to table. He must have tried to paint larger paintings, probably in water colors, and they were probably copies from bid postcards.

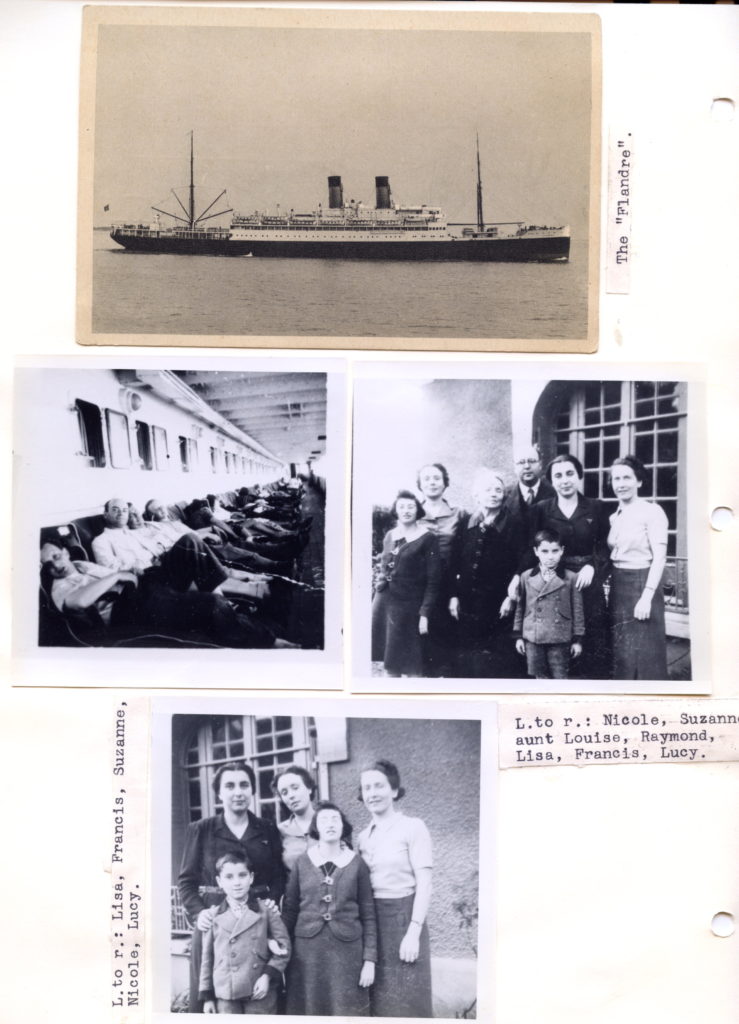

Anyway, Dr. Feingold found in his cellar two paintings signed by Adolf Hitler. He knew, of course, right away that these two paintings could be of great help to him, and he went to an important Nazi functionary whom he knew, to tell him about it, and there was great excitement. Soon people arrived to look at the paintings, and things started rolling. He was invited to see important people and he was soon asked, whether he needs some help. Of course he needed help. He wanted to emigrate to France with his family. And soon he got the passports with visas for himself, his wife, and Erich, and they traveled to Paris. It so happened that they had obtained permits for Cuba by depositing $ 500 for each of them, and also tickets for the trip by boat with the French Line, the boat Flandre, which was to sail from St. Nazaire on the 14th of October 1938. But they changed their minds and decided to stay in France and not to go to Cuba. And now they offered us in a letter to transfer the money for our trip to Cuba to us, under the condition that I pay it out to their son John Forster who was still in Vienna, and had made preparations to go with his wife Stella to India. We accepted his offer immediately.

We now changed our plans for the emigration and decided that I would go with Francis to Paris and after our arrival there I would go to the French Line, cancel the trip to Cuba for Francis, and he would be left with Lisa. This plan was the result of many deliberations. We wanted to have Francis out of that country. We thought that he was in danger there. It had happened that a Nazi had entered a classroom in a school and had beaten up Jewish children. Hedy especially was hysterical about it, wanted to save his life. Then we thought that the climate in Cuba was very bad. We had read that drinking water had to be bought in bottles. And finally, we speculated that since we had a good affidavit, she could soon get the visas for herself and the children and go to the United States, on the way stopping in Paris to pick up Francis. In the meantime, she could stay a little longer with her parents.

And there was something else. We decided to have all our possessions transported to the United States, and that Hedy would stay in Vienna till the movers had packed everything into the liftvan, to be transported via Hamburg to New York. I paid for the transportation of the liftvan the full amount in advance, and prepared a list of everything that would go into the liftvan, All that was an enormous job, and I worked on it many evenings till late in the night. All that, while I was still practicing, as patients were still coming the same as before, and I still had to make house calls. And I had to procure the passports, which meant standing in line at the different offices for many hours. I hardly moved away from the typewriter, arranging all kinds of things. There was no end to it. There was little time for reflections, for sitting together and talking about the sad things that were happening to us, the loss of everything we had achieved in hard work, put together for many, many years. Everything crushed, the family, the home, the profession.

And all the time the fear that they may come and take me away. When we heard the doorbell ring, late in the evening or early in the morning, our hearts started to beat faster. They usually came early in the morning to pick up people. I was all the time expecting it. When I went to bed, I told Hedy what to do, should it happen. I had a list of people prepared whom she should call, people who perhaps would help to get me out. Once I called Mr. Aladar von Duda, the man whose life I had saved about 9 years before. I could not reach him and he did not call me back. He was probably afraid to call a Jew and was perhaps himself in danger, as a former minister in the cabinet of Chancellor Seipel.

I also had to make arrangements with the Serotherapeutic Institute before I left. The director, Csonka, had fled, and one of the employees who had worked there in a lower position, as a bookkeeper or something like that, had become manager, and I had to negotiate with him. He agreed that he would pay my royalties to Hedy while I was away. He was in general quite friendly and cooperative. I asked him to give me a good amount of the snake venom to take along with me to Cuba. He agreed and I had to come again to get the material. I was astonished when he gave me then a round metal box, about 4 inches in diameter and about 2 ½ inches high, which was filled with a white powder. He explained that the powder contained a well-measured amount of snake venom, and that they always prepared it that way to simplify the process of making the snake venom ointment. He said that one gram of that powder, diluted in distilled water, was the amount that goes into a 5-gram tube of ointment. He did not tell me the number of mouse units of snake venom that went into a 5-gram tube of ointment and I did not ask him that question, since I knew that he would not answer it, as they had kept it to themselves as a secret. But I was confident that I would be able to find it out myself, and I was quite satisfied that he had given me that powder.

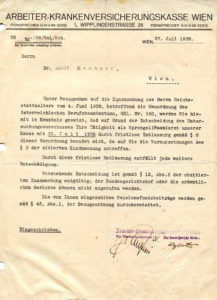

I am attaching here two letters, which I had received in those days. The first one was not dated, but arrived some time in April 1938, and here is the translation into English:

The Leader of Physicians of the Country Deutsch Oesterreich Vienna I, Weiburggasse 10/12. Tel. R-25-5-65

To Dr. Mechner Adolf, Vienna II, Taborstrasse 64.

Since within a short time Jewish physicians will be dismissed from the Kassen practice (sick fund), I want to give some of them the opportunity to give up their offices, equipment, and instruments at a price, which will be stipulated by experts, designated by me. Your practice should be taken over immediately. I am expecting your offer before May 28 of this year.

P.S. The answer is to be directed to the N.S. League of Physicians, District Vienna I. (Weihburggasse 10/12)

The Country-Leader of the League of Physicians:

Dr. Kauffmann e.h.

I never sent an answer to that letter, ignored it. Perhaps I did not realize at that time, how serious the situation was.

And here is the second letter and the translation into English:

Workers Sick Fund, Vienna, I.,Wipplingerstrasse 28.

Vienna , 27th of July, 1938 To: Dr. Adolph Mechner, Vienna.

Referring to the announcement of the governor of June 4th, 1938, regarding the reorganization of the Austrian profession, GBL No.l60, you are herewith notified on account of the decision of the investigations committee that your employment, as a district physician of our Workers Sick Fund will be terminated on July 31, 1938, by immediate dismissal, since the stipulations of paragraph 8 of the publication apply to you.

On account of this immediate dismissal there will be no further indemnification. This decision is in accordance with paragraph 12, part 5 of the above cited announcement definitive. The courts cannot be called on to intervene. The pension payments, which you have paid in, will be refunded in accordance with paragraph 43, part 1 of the regulations.

Workers Sick Fund Registered.

The Representative

The commissary leader (signed)

(signed)”

In another letter, which I don’t have anymore or cannot find, I was notified that I will not be allowed to practice medicine after September 30, 1938. This was the day, as will be seen later, when I left Vienna.

The day of our departure came closer. I did not have the time to pack our baggage, had to leave that to Hedy. Only important papers, documents, I had to select myself, also some instruments, which I thought I could use in the emigration and I was so right. Before we left, I went to my tailor and had him make three white suits for me for the tropical climate. I had forgotten to order a new tuxedo in time, and left without it, but it was sent to me to my address in Paris and it arrived in time, before I left for Cuba, as I needed it on the boat, as a first-class passenger. Fortunately, we had our passports already, for quite some time, and only Francis’s name and picture had to be added to my passport, which was relatively easy. Unnecessary to say that I left a good amount of money with Hedy.

The only thing I did not have yet were the tickets for the boat. The French Line had an office in Vienna, near the opera building, and they were advised from Paris by telegram and letter to write out the tickets for the boat Flandre for me and Francis. But they made it difficult for me, postponed it for another day, each time I went there.

The night before I left, I had taken a big trunk packed with my belongings to the train station to have the contents inspected, so that it would go with the train the next day with me. Everything was in order.

I went the next day early in the morning to the French Line, hoping to get the tickets fast. But I soon saw that I had there to deal with two very difficult people, a middle-aged man with a swastika in his lapel and a young woman. The man told me that he was against it that I go to Cuba, and things like that. He then asked me to come back in an hour, and said that he will write out the tickets in the meantime. When I came back, it was again the same situation, that man trying to convince me that I should not go to Cuba. I then got very angry and shouted at them and said that they will be responsible for the consequences, since my baggage was already in that train, and that I will sue them and denounce them at the French Line. That had an effect, and in a few minutes I had the tickets. To my amazement, I saw this young woman from the French Line in the train to Paris. I still don’t know why they did not want to write out the tickets for me and Francis for the boat.

I rushed home by taxi, had just time to say good bye to everybody and to pick up Francis and two valises. It was a heartbreaking scene, when they all—my in-laws, Hedy, and Aunt Klemi—stood there on the sidewalk while we jumped into a taxi and went off, waving our handkerchiefs in the air. We arrived just in time at the train station Westbahnhof, about 5 minutes before the train left. My uncle Martin Sobel and Aunt Clara were there to bid farewell to us. I could hardly say a few words to them, as the train had started to move.

We had a relatively nice ride in a first-class coupe, with fine upholstered seats, and since we were alone there, we sat at the window across each other, with a little board between us. I soon started to read books to Francis, and in general rested after the hectic hours that preceded our trip.

I was, of course, worried that something might go wrong at the border. After an hour or two, in one of the stations, a high German officer joined us in the coupe, later a few more people. In the evening the train reached Munich and there was an enormous crowd of people at the station shouting, applauding, and singing. It was the 30th of September 1938, the infamous day of Munich, when Hitler, Mussolini, Neville Chamberlain, and Daladier had met there and agreed to sacrifice Tchechoslovakia, to cede the Sudetenland to Germany. At that moment, when we arrived at the station, Hitler took leave of Mussolini. Daladier must have been in the same train with us, going back to Paris. He must have worried about what kind of reception the French people would give him. We saw it right after our arrival in Paris, since our way took us to the Champs Elisée. He probably had not expected it, but he got a triumphal reception, with enormous masses of people applauding and shouting. Daladier was surprised, as we later read in the newspapers. We happened to see and hear it from our car.

After Munich, near the German border, I saw woods and I told Francis, “You know where we are now? We are in the Schwarzwald.” And he said with a loud voice, “In the Schwarzwald? That is where the Danube arises.” The German officer and some other people in the coupe smiled. We came close to Kehl, the German border town on the Rhein, across Strassbourg. An inspection officer came and I felt my heart beat in my neck. He demanded to see the passport and the paper called Steuerunbedenklichkeitsbescheinigung which showed that I did not owe any taxes. Another man examined our valises. Everything was found in good order and they left. When we crossed the bridge over the Rhine, a stone fell from my heart. I did not sleep much that night, was too excited. In the morning, I was all the time at the window, looking at the French landscape.

I had heard the family story that Josef Feingold received the Hitler watercolors from a client as payment for legal services, but other sources mention him by name as a customer/patron of Hitler and the framer Samuel Morgenstern in Vienna before World War I.

The Wikipedia entry for Samuel Morgenstern says: “Hitler regularly supplied Morgenstern’s business with his pictures until his emigration to Germany in May 1913. Morgenstern later justified this purchase decision with the fact that in his experience it was easier to sell picture frames if they already contained a picture on the sales shelf as illustrative material, so that the customer could get an impression of their effect. The motifs of Hitler’s paintings were mostly historical views in the style of Rudolf von Alt. Morgenstern also had the Viennese lawyer Dr. Joseph Feingold. His wife, Elsa, née Schäfer, liked the pictures of Hitler, and he bought several for his apartment and law firm. After the invasion of the German Army, the pictures were picked up by the Gestapo. Josef and Elsa Feingold were arrested while fleeing in the Nice area, deported to Auschwitz via Drancy internment camp, and murdered.”

From Brigitte Hamman’s book “Hitler’s Vienna: A Portrait of the Tyrant as a Young Man”: “One of Morgenstern’s main clients was the lawyer Dr. Josef Feingold, according to the person who interviewed him in May 1938, ‘apparently not entirely Aryan, but certainly leaving the impression of being respectable, a war veteran.’ He had his law offices downtown, near Stephansplatz, and supported a number of young painters sent by Morgenstern. He bought a series of old views of Vienna by Hitler, which he had framed by Morgenstern in the style of Biedermeier.”

Footnote 102: “According to the Registration Office, Dr. Feingold was born in Vienna in 1878, Jewish, married. According to Lehmann’s residence listing of 1910 he still lived in Leopoldstadt at the time (5 Kleine Schiffgasse), and his law office was at 5 Rauhensteingasse. Before his emigration to France in 1938 he lived in the Third District, at 6/1/9 Beatrixgasse.”

Footnote 103: “When the search for Hitler’s paintings began in the 1930s, Feingold no longer had any; after the downsizing of his offices, he said, he had no longer had any use for them and given them away as presents–four alone to his hairdresser’s daughter, who sympathized with the National Socialists. According to the hairdresser Mock’s report to the NSDAP archive in 1936, these were views of the old Schönbrunn gate, the Ratsenstadl, Auersperg Palace, and the old Burgtheater, all signed ‘A. Hitler.’ Feingold did not tell his curious interviewer anything about young Hitler. According to the Registration office, he left Vienna on 4 August 1938, heading for France.”