1941-1943

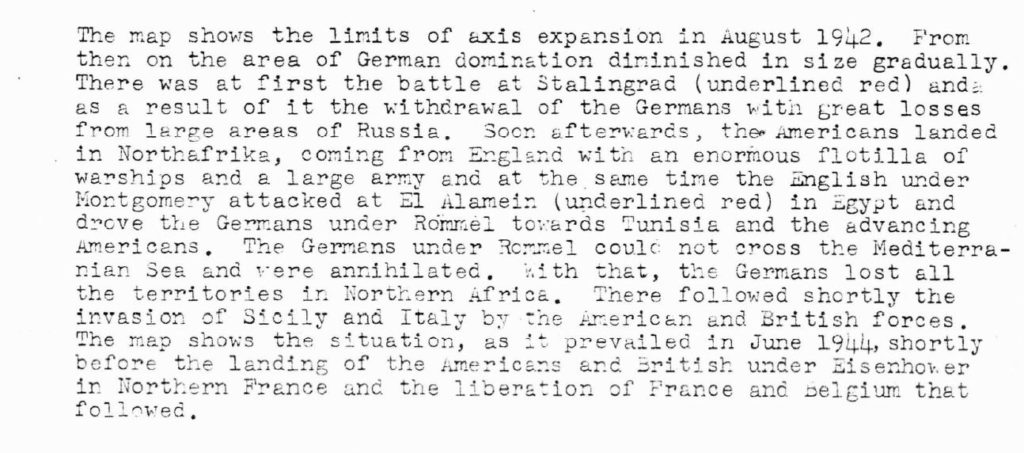

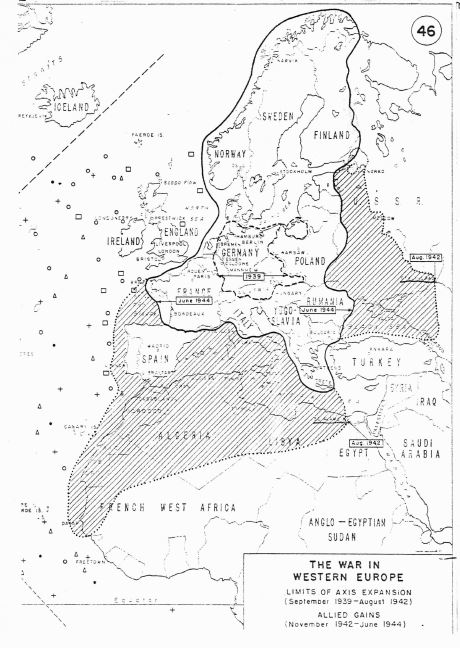

I had discontinued the description of the major events in the war after the attack of Pearl Harbor, as continuous description of my own affairs and those of my family would have been difficult to maintain. I will now bring these major events in the war in chronological order. I had mentioned some of the events in the far East, serious reverses, first of the American navy, also of the English navy, then reverses of Japan in sea battles. In Russia, the great offensive of the Germans took them deep into the Caucasus and they also crossed the Don River and opened an offensive against Stalingrad on the Volga River on August 22, 1941. American and British supplies were shipped to Russia by railroad through Iran. The Germans had penetrated Stalingrad on September 14th but then Russian forces counterattacked northeast of Stalingrad and ten days later opened a second thrust southeast of the city. It was an enormous pincer movement, which resulted in a debacle for the Germans. 22 German divisions were cut off at Stalingrad and 500.000 men were killed and captured. On November 8th, 1942, American and British expeditionary forces: landed in French North-Africa in the greatest amphibious invasion hitherto attempted, with alltogether 850 ships. At about the same time, Allied forces under general Bernard Montgomery started an offensive in El Alamein in Egypt against the German forces under general Rommel, resulting finally in the annihilation of the German forces. Following that, American, British, and Canadian forces invaded Sicily on July 10th, 1943 and on September 3rd crossed the Straits of Messina and landed in southern Italy. Later, bigger contingents of troops landed south of Rome. On June 6th, 1944, Allied forces landed in Northern France near Cherbourg, an enormous undertaking with strong naval support, an armada of 4OOO ships and over 10,000 aircraft. They succeeded to occupy within a week a strip of beach, 60 miles long. The beachhead was later enlarged in severe fighting. Cherbourg was taken, later Caen. In another amphibious operation, the Allies affected successful landings on the French Mediterranean coast between Marseille and Nice. The Germans were there on the run. On August 24th, 1944, the citizens of Paris rioted against German forces of occupation, as Allied armed divisions crossed the Seine and approached the capital. French Forces of the Interior, which had been organized for underground resistance arid suppliers with arms, rose against the retreating Germans. On September 2nd, Allied forces, which had penetrated into Belgium, liberated Brussels. On September 12th, the American First Army crossed the German frontier near Eupen and north of Trier. The American Seventh and French First armies, sweeping up the Rhone Valley from beachheads on the Riviera coast, joined the American Third Army at Dijon. The American, British, and French Forces were re-organized in liberated France for an assault on Germany.

The German Supreme Commander in the West, general Karl von Rundstedt, under orders from Adolf Hitler, dislocated Allied preparations by a sudden drive against thinly held American lines in the Belgian and Luxembourg sector. Suffering heavy losses, the Allied forces were driven back to the Reuse, but they rallied to attack strongly on both sides of the “bulge” and the Germans were checked before the close of December. With the opening of 1945 the American, British, and French drove into Germany from the West, coordinated with the rapid and powerful Russian thrusts from the Danube Valley, Poland, and East Prussia, fused into one vast combined operation.

Military supplies from Great Britain and the United States had helped materially to arm the Russian forces for the campaigns of 1943. Part of the equipment went by northern convoy routes to Archangel, part in Russian ships to Vladivostok, part via the Persian Gulf. Shipments through Iran increased to 100.000 tons a month by autumn of 1943 consisting of 6500 airplanes, 138.000 motor vehicles, shiploads of steel, and industrial machinery for Soviet arms factories. Anglo-American bombing was crippling German industry, greatly reducing the output of German planes, depriving the Germans of their superiority in the air. The Germans were driven back on a wide front. On November 6th, Kiev was recaptured. In March 1944, the Russian drive brought them to the Rumanian border.

During the last 4 months of fighting, Allied air squadrons roamed Germany almost at will, destroying communications, obliterating plants and stores, and wrecking many of the remaining German aircraft on the ground, where they lay helpless for lack of fuels and repairs. Opening a powerful drive into Poland, the Russians took Warsaw, swept into Krakow and Lodz and by February 20th were within 30 miles of Berlin. On February 7th, the Yalta Conference took place between President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill, and Marshall Stalin, to plan the final defeat and occupation of Germany. At that time, the United States Third Army had crossed the German frontier at ten points and continued its advance toward the Ruhr Valley, entered Trier and Cologne. By April 11th, the United States 9th Army had reached the Elbe River. Eight days later, the Russians fought their way into Berlin, and advanced units of the American and Russian armies met on the Elbe at Torgau. The German divisions in Italy surrendered.

President Roosevelt had died a few weeks before on April 12th, 1945, and Harry S. Truman became president. Mussolini, trying to escape into Switzerland, was captured and shot by Italian Anti-Fascist partisans on April 28th, and Adolf Hitler committed suicide on or about May 1st in the Reichschancellery in Berlin. On May 8th, President Truman for the United States and Prime Minister Churchill for Great Britain proclaimed the end of the war in Europe (V-E Day). An Allied Control Committee, including General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Field Marshal Sir Bernard L. Montgomery and Marshall Gregory K. Zhukov, assumed full control throughout Germany. German territory was delimited in four zones of occupation under American, British, Russian and French military administration.

Important parts of the war were not included in this description of the war, since it would have required much work and discontinuation of the family biography which was the main object. Not included was the naval war, the war in Asia and in the Pacific, which ended with the surrender of Japan, after two atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In the aftermath of the war the United Nations Organization was formed as of October 24th, 1945 and the first session of the U.N. General assembly opened in London on January 10th, 1946 with 51 nations attending. On July 29th, 1946, a peace conference of the 21 nations, which waged war against the Axis in Europe, met at Paris to discuss the draft treaties for peace with Italy, Rumania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Finland. On February 10th, 1947, the Peace Treaties were signed in Paris. Italy lost a small border region to France, her Adriatic Islands, and most of Venetia Giulia to Yugoslavia, and the Dodecanese Islands to Greece. She also lost sovereignty over the North-African colonies and agreed to the creation of the Free Territory of Trieste, and also to the payment of $360 million in reparations. Rumania lost Bessarabia and the Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union, but received back all of Transylvania. Finland ceased the port of Petsamo, high up in the North, to the Soviet Union. On April 4th, 1949, the North Atlantic Treaty was signed in Washington by the foreign ministers of Great Britain, France. Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Italy, Portugal, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, the United States, and Canada. It provided for mutual assistance against aggression within the North Atlantic area and for close collaboration in matters of military training, arms production, and strategic planning, under the direction of the North Atlantic Council. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed commander in chief of the North Atlantic Treaty forces, with headquarters in Paris.

With the total defeat of the Hitler regime, no German government remained. Instead supreme authority was vested in an Allied Control Council of Great Britain, France, the United States, and the Soviet Union. Each of these powers administered its own occupation zone, with the Soviet Union holding the region east of the Elbe. The former capital, Berlin, was likewise divided into four sectors.

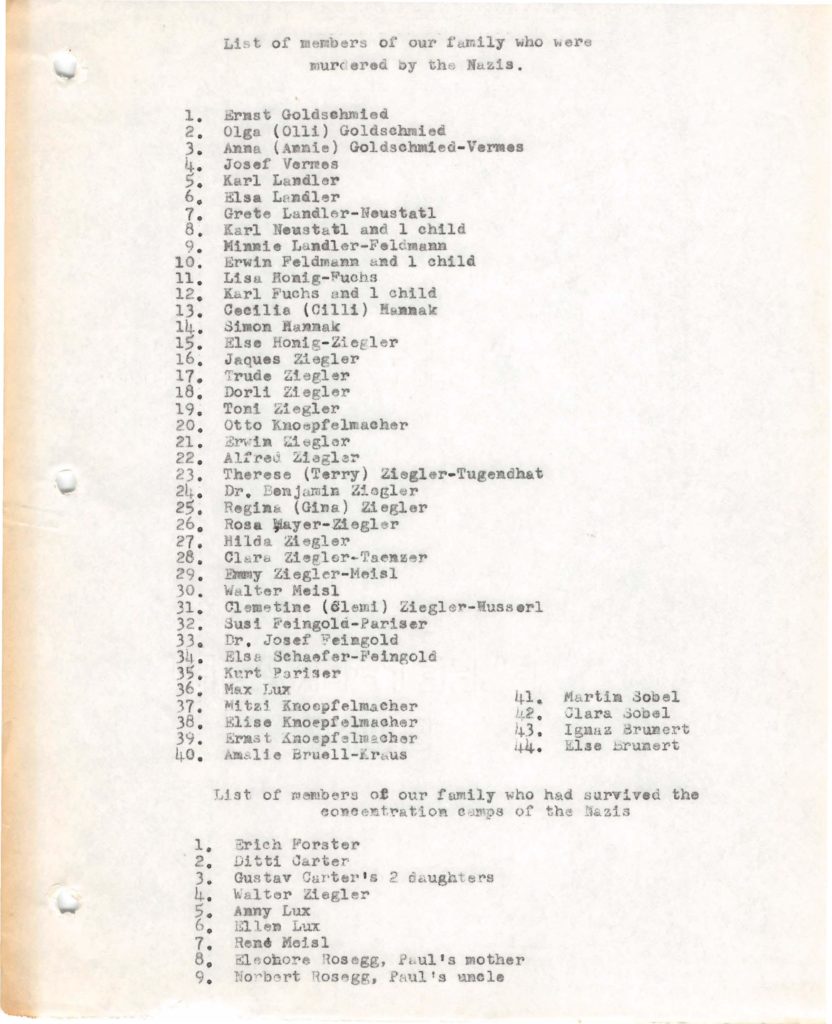

The most immediate measures of the victors were concerned with the liquidation of the Nazi system. On November 20th, 1945, the trial of major Nazi leaders opened at Nuremberg before an Inter-Allied Tribunal. Voluminous evidence was presented to prove the plotting of aggressive warfare, the extermination of civilian populations (especially the Jews), the widespread use of slave labor, the looting of occupied countries, and maltreatment and murder of prisoners of war. A complete description of the war with all details is contained in the book “The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich” by William L. Shirer, the reading of which I recommend to those who are interested in it. I have added here copies of a few of the last pages of that book as they contain the sentences meted out in Nuremberg, and I am citing here parts of these pages:

“Attired in rather shabby clothes, slumped in their seats, fidgeting nervously, they no longer resembled the arrogant leaders of old. They seemed to be a drab assortment of mediocrity. It seemed difficult to grasp that such men, when last you had seen them, had yielded such monstrous power that they could conquer a great nation and most of Europe.

There were twenty-one of them in the dock. (Dr. Robert Ley, head of the Arbeitsfront, who was to have been a defendant, had hanged himself in his cell before the trial began. He had made a noose from rags torn from a towel, which he had tied to a toilet pipe). There Goering, eighty pounds lighter than when last I had seen him, in a faded Luftwaffe uniform without insignia ….. Rudolf Hess, who had been the Number Three man before his flight to England, his face now emaciated, his deep-set eyes staring vacantly into space, feigning amnesia but leaving no doubt that he was a broken man . . . . Ribbentrop, at last shorn of his arrogance and his pompousness, looking pale, bent and beaten ….. Keitel, who had lost his jauntiness; Rosenberg, the muddled party “philosopher,” whom the events which had brought him to this place appeared to have awakened to reality at last. Julius Streicher, the Jew-baiter of Nuremberg, was there. This sadist and pornographer, whom I had once seen striding through the streets of the old town brandishing a whip, seemed to have wilted. A bald decrepit-looking old man, he sat perspiring profusely, glaring at the judges and convincing himself – so a guard later told me – that they were all Jews. There was Fritz Sauckel, the boss of slave labor in the Third “Reich, his narrow little slit eyes giving him a porcine appearance. He seemed nervous, swaying to and fro. Next to him was Baldur von Schirach, the first Hitler Youth Leader and later Gauleiter of Vienna, more American by blood than German and looking like a contrite college boy who has been kicked out of school for some folly. There was Walther Funk, the shifty-eyed nonentity who had succeeded Schacht. And there was Dr. Schacht himself, who had spent the last months of the Third Reich as a prisoner of his once revered Fuehrer in a concentration camp, fearing execution any day, and who now bristled with indignation that the Allies should try him as a war criminal. Franz von Papen, more responsible than any other individual in Germany for Hitler’s coming to power, had been rounded up and made a defendant. He seemed much aged, but the look of the old fox, who had escaped from so many tight fixes, was still imprinted on his wizened face. Neurath, Hitler’s first Foreign Minister, a German of the old school, with few convictions and little integrity, seemed utterly broken. Not Speer, who made the most straightforward impression of all and who during the long trial spoke honestly and with no attempt to shirk his responsibility and his guilt. Seyss-Inquart, the Austrian quisling, was in the dock, as were Jodl and the two Grand admirals, Raeder and Doenitz – the latter, the successor to the Fuehrer, looking in his store suit for all the world like a shoe clerk. There was Kaltenbrunner, the bloody successor of “Hangman Heydrich,” who on the stand would deny all his crimes; and Hans Frank, the Nazi Inquisitor in Poland, who would admit some of his, having become in the end contrite and, as he said, having rediscovered God, whose forgiveness he begged; and Frick, as colorless on the brink of death as he had been in life. And finally Hans Pritssche, who had made a carreer as a radio commentator because his voice resembled that of Goebbels, who had made him an official in the Propaganda Ministry. No one in the courtroom, including Fritzsche, seemed to know why he was there – he was too small a fry – unless it were as a ghost for Goebbels, and he was acquitted. So were Schacht and Papen. All three later drew stiff prison sentences from German denazification courts though, in the end, they served very little time. – Seven defendants at Nuremberg drew prison sentences: Hess, Raeder, and Funk for life, Speer and Schirach for twenty years, Neurath for fifteen, Doenitz for ten. The others were sentenced to death.

At eleven minutes past 1 A.M. on October 16th, 1946, Ribbentrop mounted the gallows in the execution chamber of the Nuremberg prison, and he was followed at short intervals by Keitel, Kaltenbrunner, Rosenberg, Frank, Frick, Streicher, Seyss-Inquart, Sauckel and Jodl. – But not by Hermann Goering. He cheated the hangman. Two hours before his turn would have come he swallowed a vial of poison that had been snuggled into his cell. Like his Fuehrer, Adolf Hitler, and his rival for the succession, Heinrich Himmler, he had succeeded at the last hour in choosing the way in which he would depart this earth, on which he, like the other two, had made such a murderous impact. ”

A trial of 28 alleged war criminals was conducted (1946 -1947) by an eleven-nation tribunal in Tokyo. Evidence similar to that presented against the Nazis brought death sentences to Tojo and others. The U.S. Supreme Court refused an appeal, based on the grounds that the international court was unlawful. Although exact statistics are not available, it is estimated that by 1950 about 8000 persons were tried and about 2000 executed. Of the German war criminals, Rudolf Hess was convicted to lifetime prison and is still a prisoner in Spandau near Berlin in the Russian zone of occupation.

That Mussolini and his mistress were captured near the Italian-Swiss border, when they tried to escape to Switzerland and killed by a firing squad, I may have mentioned already. The bodies of both were brought to Milano and hanged by their feet, with their heads down, in the center of the city. In France, Marshall Petain was condemned to death, but on account of his high age the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. But Pierre Laval received a death sentence, and was executed by a firing squad.

In Germany, in addition to the 22 top criminals, thousands of lesser Nazis were removed from office and held for trial. The Control Council approved the transfer of 6,650,000 Germans from Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the German region beyond the Oder-Neisse line, which had been handed to Poland at the Potsdam Conference, pending a final peace settlement. The International Tribunal at Nuremberg announced its decisions on September 30th, 1946. The Nazi Leadership Corps, the S.S., the Security Police, and the Gestapo were found criminal organizations, while the S.A., the cabinet, and the General Staff were acquitted.

The conferences for a peace agreement with Germany were a long-drawn affair. There was the Potsdam Conference on July 17th to August 2nd, 1945, in which President Truman, Prime Minister Churchill, and Generalissimo Stalin participated. For Germany the decisions reached implied: 1) Disarmament and demilitarization; 2) Dissolution of National Socialist institutions; 3) Trial of war criminals; 4) Encouragement of democratic ideals; 5) Restoration of local self-government and democratic political parties; 6) Freedom of speech, press, and religion.

Economic restrictions implied: 1) Prohibition of the manufacture of war materials; 2) Controlled production of metals, chemicals, and machinery essential to war; 3) Decentralization of German cartels, syndicates, and trusts, etc. The Conference further ordained “that Germany be compelled to compensate to the greatest possible extent for the loss and suffering that she has caused to the United Nations….” There were disagreements between Russia and the Western Allies in the conferences which followed.

< previous chapter | next chapter >