The first time I met Erich was through a mutual friend of ours, Dr. Fritz Jerusalem, who went to fight in Spain in the Civil War in 1936, on the side of the Socialists, and he perished in that war. The plane was highjacked. They knew that he was in that plane, and he was shot. Erich was a colleague of this Dr. Jerusalem who had a well established practice, which he had rented from a doctor’s widow, the widow of Dr. Itzkowitz in Lerchenfelderstrasse. Dr. Jerusalem needed a replacement there, when he left for Spain. Erich took over this practice, and that was beside his father’s practice.

I had come back from a vacation in Dalmatia with a backache and chills. My sister called up the office of Dr. Jerusalem, not knowing that he had left, and the call was referred to Erich. He came to our house and examined me, and he prescribed something. I lived at that time in the 9th District at Glasergass 20. I had lived there all my life. I remember that he commented at my brown back, which was brown from sunburn. That was the first time I met him.

We used to have Wednesday night jours in our house; my sister and I lived together, and we had quite a large circle of friends, who came every Wednesday night. My parents had died, when I was about 16, both of them within a year. My mother died of cancer. My father had come back from the first World War with a pneumonic flu, and he later developed Parkinson’s disease. He was a sick man all the time. My father survived my mother only by 9 months.

I was born in 1917, and my mother died in 1934, when I was about 16 years old. We had a very good aunt. Every Wednesday, we had open house, it was called jour fixe. There were great numbers of young intelligent people, who came. They usually had discussions about socialism, and, of course, Leo Zimmermann was there already, Fritzi’s husband, when he was not in jail. It was under Schuschnigg, and Leo was often in jail. Then he was put in a concentration camp in Woellersdorf, and Fritzi finally got him out, but there was an understanding that he would leave Austria and that he would never come back. They were married at that time already. It was difficult to get him out of the concentration camp, and since she had not the papers ready, they allowed him to leave under guard and they put him only across the border and he went to Paris. Fritzi remained with me in Vienna. We had a business there, the business of my parents, which we continued after they died. It was a wholesale button business for tailors and manufacturers, only men’s buttons.

She was supposed to follow Leo later on and I was supposed to carry on the business alone in Vienna. Every 3 or 4 months she intended to come back to Vienna to help me with the business. But by that time, it was already 1938, and Leo kept writing to her to come to Paris, but she postponed it. Finally, one night, at 4 o’clock in the morning, he phoned and told her, when you don’t come in today’s train, you don’t have to come at all. In Paris, they knew what was coming. It was on the first of March, and she took the train the same day and left. So, I was left alone to carry on the business.

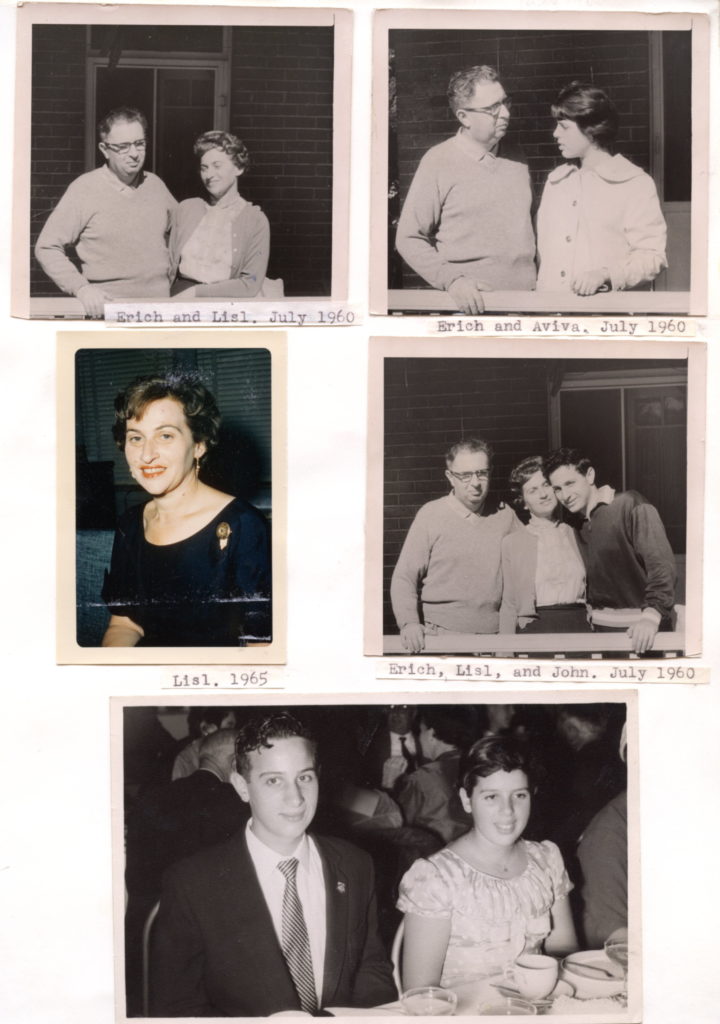

To come back to Erich, his appearance on the scene, he became involved in the Wednesday night jours – there were some 14 people there – and he came quite often, and it finally became a love affair. I used to go to the Taborstrasse every Sunday, I used to take a taxi, we had lunch there, and Erich’s father was very nice to me, and Erich’s mother liked me very much, was very friendly. The old aunts used to be there too. Lisa knitted me a beautiful pullover. Wilfred was also there.

Then came the Nazis, and we decided, of course, to go away. It was quite a difficult undertaking, since nobody could get any visa. First Lisa left, it was in May. Erich left on the 13th of August. He was supposed to get a French visa, but the French consul did not want to give him the visa. Through Fritzi, he finally got a visa for Poland.[1] He took a plane for Warsaw,[2] which landed in Prague. Othmar Ziegler, a cousin, got a telephone call from us, to be at the airport and see to it that he could get out of the plane and stay in Prague. But the airplane left without him and he was arrested. But Othmar Ziegler had very good connections, got him out of jail right away, guaranteed for him, and they allowed him to stay in Prague for 3 days. In the meantime, Othmar worked it out, and he got an extension for 14 days. There was another cousin, Alfred Ziegler, in Bruenn, who was consul for Uruguay, but he had to promise him that he will not go to Uruguay. “This will,” he said, “take you out of Czechoslovakia, and I will give you a transit visa to Belgium to catch the ship in Antwerp” and he also got him a ticket for the ship from Antwerp to Uruguay. He arrived in Belgium in Antwerp, and there he took a train to Brussels, and sent the ticket back to Alfred in Bruenn. That was the arrangement. He had to send it back, because Alfred had paid for the ticket. He then cancelled the trip from Antwerp to Montevideo, Uruguay.

Now there is another interesting story. I wanted to go on

the same plane, because in the meantime I had got a domestic permit to England, as a domestic servant. I got this permit through a Jewish organization, to work for a Jewish family in England. I intended to leave on the same plane with Erich to Prague and from Prague to catch another plane to Paris. I could have gone on the plane with Erich to Prague, but it happened that the plane from Prague to Paris was booked up. That meant that I could not join him on his flight to Prague. I had written to Fritzi that I will come on that plane from Prague to Paris. Fritzi had told all our friends in Paris that I am coming on this plane. This was the plane that Max Pallenberg, the famous actor, was in. That was the plane that crashed, and only because I could not get a ticket I survived.

I then had to stay one day longer in Vienna and decided to take the next train from Vienna directly to Paris, and you, Adolph, took me to the train, the Westbahnhof. I had sent a cable to Fritzi and she knew that I was not on the plane. I then stayed in Paris for about a week. I had a visa for England and also a transit visa for France and that visa was only good for one week. While in Paris, I went to the Plateau d’Avron and met Lisa. Then I went by train to England. I took the job there and it was quite a difficult job. These people were very poor people. I did not have the intention to stay in that job anyway. Everybody was in Brussels then, a favourite cousin of mine with his wife, and another cousin. I stayed with that family in England for about 6 weeks, and I had connection with Erich only by mail. We decided that I should come to Brussels. I got from the employment office the permission to leave the country for a week and come back again. I got a re-entry permit. But the Belgians were very nice at that time, and they did not make me go back. So, I stayed with Erich. He was with the refugee committee as a doctor and he was not paid for his work, but got like all the other refugees support and a small amount more, because he took care of the refugees, and I worked for a family there in Belgium. A very nice family befriended us, a Jewish family from Lodz by the name of Koppelmann. They looked after us, and finally made a wedding for us. We got married on November 26th, 1938. It was a civil wedding at the marriage office. It was a double wedding with a doctor Fuchs and his bride. We had decided to get married together, but we had to postpone the wedding, because Dr. Fuchs was put in jail in the meantime. Since enormous numbers of refugees came to Belgium at that time illegally, they arrested many of them to bring the influx to an end, and they put many of them also back over the border. First they put them into detention camps. But this Dr. Fuchs and his bride had come with papers, officially, and they could stay.

Erich had written to Mr.Star to Australia, and he asked him to get him a permit. He had an American affidavit, but had trouble at the consulate. Mr. Star went to Canberra and had a difficult job there, but succeeded finally to get a permit there for Dr. Ziegler and his wife. We got married on the 26th of November on a Saturday, and on Monday, the 28th of November a letter came from Canberra with our permit. That was a very nice wedding gift, the only one we received, but it was a good one.

We had to look around to get our tickets to go to Australia, and to get 200 pounds landing money. We had some jewellery, belonging to the family, to my sister and me, which we sent to London to be sold, but we got very little for it, only 40 pounds. The rest of the money, Maurice[3] Ziegler loaned to us; he sent us the money and we promised to send it back. He sent us 200 pounds and we had 40 pounds of ours. He said we can keep 30 pounds as a wedding present, and the rest we sent back to him as soon as we arrived in Sydney. The Joint Committee paid for our fares and we paid it back in Australia in monthly rates. Very few of the refugees did that.

We arrived in Sydney on the 21st of June. Before we left, we saw Lisa and Francis in Paris, we bought him a bird at the market, had quite some fun with the bird. The French were so nasty, did not want to give us transit visas, to get to the ship in Marseille, but not until the very afternoon around 6 o’clock we left to go to Paris. At 4 o’clock we did not have our visa, it was really terrible. While I was packing, Erich went to get finally the visas. I was packing and I had this bird. The bird flew out of the cage, and it was fun and games, but we caught the bird again and we took the bird to Paris for Francis. We stayed one night in Paris at my sisters home and Lisa and Francis were there. They were already living with my sister, it was about the 15th of May, when we arrived in Paris. We then went to Marseille. From there we went to the Suez Canal, through the Red Sea to Aden. From there we went to Bombay, then Colombo in Ceylon. Then to Fremantle, around the south shore to Adelaide, Melbourne and then Sydney, where we arrived on the 21st of June, 1939. When we arrived there, it was awful. Everybody was there to pick up the people, but for us nobody came. Mr. Star was not there at the boat. We were sitting there for hours. The ship had arrived at about 6 o’clock in the morning and he arrived at about 10 o’clock. He put us in a very bad position.

When we got to Bombay, we had only a few pounds that were our own, and we bought a sari, that the Indian women wear, draped around like Mrs. Ghandi, a beautiful thing, and we thought if there was a Mrs. Star, we would have a little present for her. If there is no Mrs. Star, I wou1d keep it for myself, and if there was a little boy – we knew he had a son -so we bought some chocolate, Tobler. You can imagine what happened, it was melted. And for Mr. Star, Erich had a tie pin. Erich thought, he will give him the tie pin and nothing else. So, Mr. Star arrived and apologised for being late. Mr. Star did not have a telephone in his house, otherwise he could have let us know that he will be late.

So, he took us home in a taxi, and I will never forget, how he started to tell us that we should not worry in case his wife is antagonistic against us, because she lost her brother and his family in Poland, and she may resent us. That was just a fabrication and very silly. He did not know his wife at all. We met her, she was a very fine person, and she would never have such thoughts in her mind; and she made us very welcome, she was very friendly. All their friends, all the neighbors came in, it was a sort of small community of Russian and Polish Jews, who were very nice to us. And it happened that one of their next door neighbors, Mr. Cantor and their maid, had chopped one finger off the day before, and they were very badly in need of somebody to take care of their 7 year old child called Aviva. They did not say anything. Then, when they saw that we were quite normal people, they asked me whether I would like to help in the house and look after the child, because she was in business. So, I had a job on the first day I arrived. We later became good friends, our best friends, and they are still our best friends. She called me up the other day, from Toronto, on her way through. She was staying with her daughter in Toronto, and just got home, a week ago today.

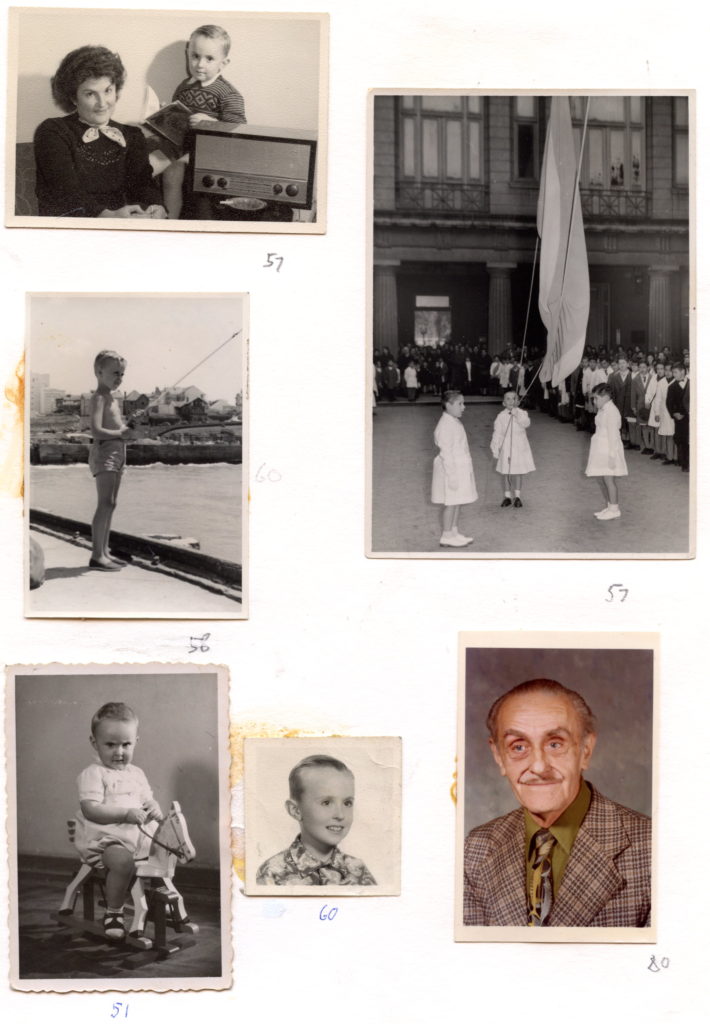

Erich did not work for 3 years. The situation was rather grim, because, under the existing law, Austrian doctors were not allowed to practice in Australia. The only way was that they would have to take a 3 years course at the University. He enrolled to do that; I don’t know where he would have gotten the means to do it, but we tried, we thought we will give it a go. But they didn’t accept him in Sydney, they accepted him in Adelaide. To go from Sydney to Adelaide for exams, twice a year, was quite a ridiculous thing, but he said he would study.

But then the war broke out and we became enemy aliens. So, enemy aliens were not allowed to go out of their suburbs, let alone to go to a different city. So, that was out. We had to report to the police once a week. Then the poor Australians did not understand what was going on. You could not blame them. Nobody blamed them for what they did, but they were really in trouble, as they did not know what a friendly alien was and what an enemy alien was. But finally they classified us as friendly aliens, and that was the time when the Australian doctors joined up to go overseas. The war broke out in September, the Australian doctors joined up and the country was suddenly left without doctors, particularly the country as such, in the bush. So, they created a medical emergency service, and brought up a regulation, under which they intended to let the foreign doctors practice under license, only at a given place and not where they chose to practice, but at one particular spot, and to enable them to do that, they had to undergo examinations and they said they will give them three written exams, just to see how fluent they were with the language. But they tricked them there too, when they finally came to the exams, they gave them 3 written exams, 3 hours in a row. It was not easy and not nice, it was a trick. Because, although they needed the doctors, they were afraid and jealous of the foreign doctors. Only a third of all the doctors that sat for the exams, passed them, but Erich was one of them and he passed, and he got a job.

The job was in the bush, 240 miles from Sydney, in Gresford. It was an agricultural area, a township of 300 people, a radius of 30 miles, and population within the radius about 3000 people. The nearest hospital was 27 miles away, in Maitland, and the nearest doctor was 27 miles away. There was no pharmacy, there was nothing. He was employed and paid like an army major, was paid by the government. The money that came in were collected by us and sent off to the government. He got his salary each week or so. It was very little, but he had the house for nothing, we did not pay any rent. It was a house, where a doctor had lived before, and had a practice. But there was actually nothing there, since the doctor had left some time before. There was a desk, but he had a few instruments of his own. The government supplied a car. He had to learn how to drive and it was quite hard. He could not manage very well. The people were quite antagonistic. It was a difficult situation for us, because they had never seen a foreigner in their lives, they had never seen a Jew in their lives. We were lucky that we did not hide the fact that we were Jews, which put us actually on an island. In Australia it was so that the different religious arrivals, the Protestants and the Catholics, would not socially meet. They tolerate each other if they had to. But we were lucky, we were friends with both, we were neutral. There were many churches, there was one right across the road from where we were, it was a Catholic church, and people used to go to church, and afterwards they came to the doctor, they did not do it in reverse. So, what happened was: They went on Sunday to Sunday mass at 7 o’clock, and then they used to come to the doctor and have breakfast at our house; we had open house. After a while, they got used to us and we got used to them, and I have always been rather friendly. They liked Erich. As regards to medicines: We had a dispensary and we made up the bottles and I helped him. He sent stock lists to Sydney, and they sent the material by mail.

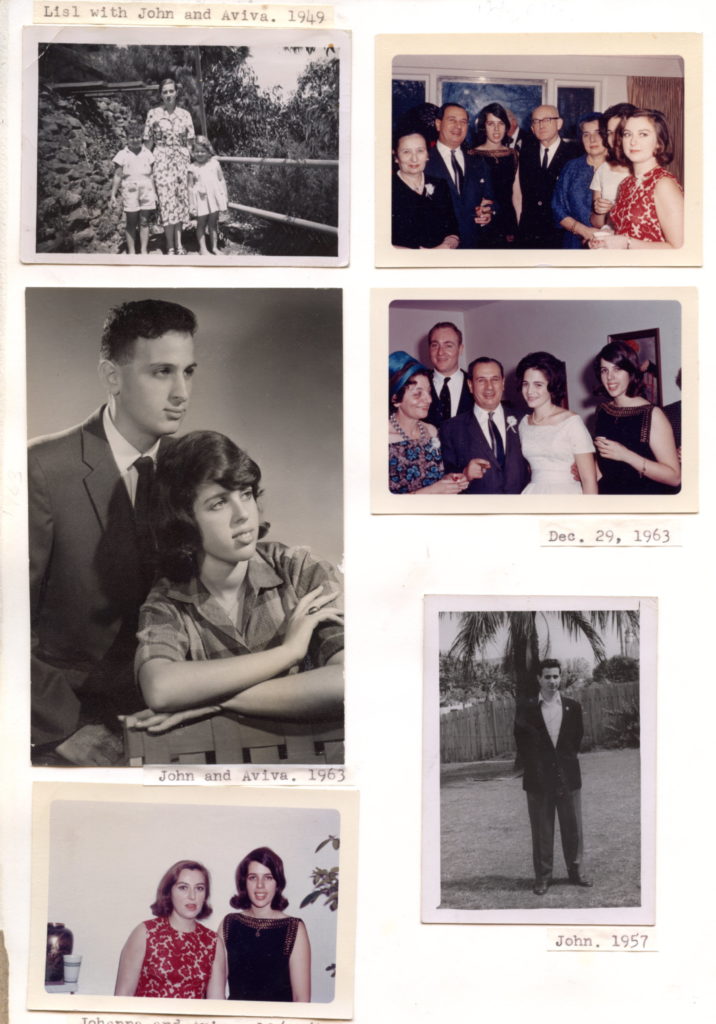

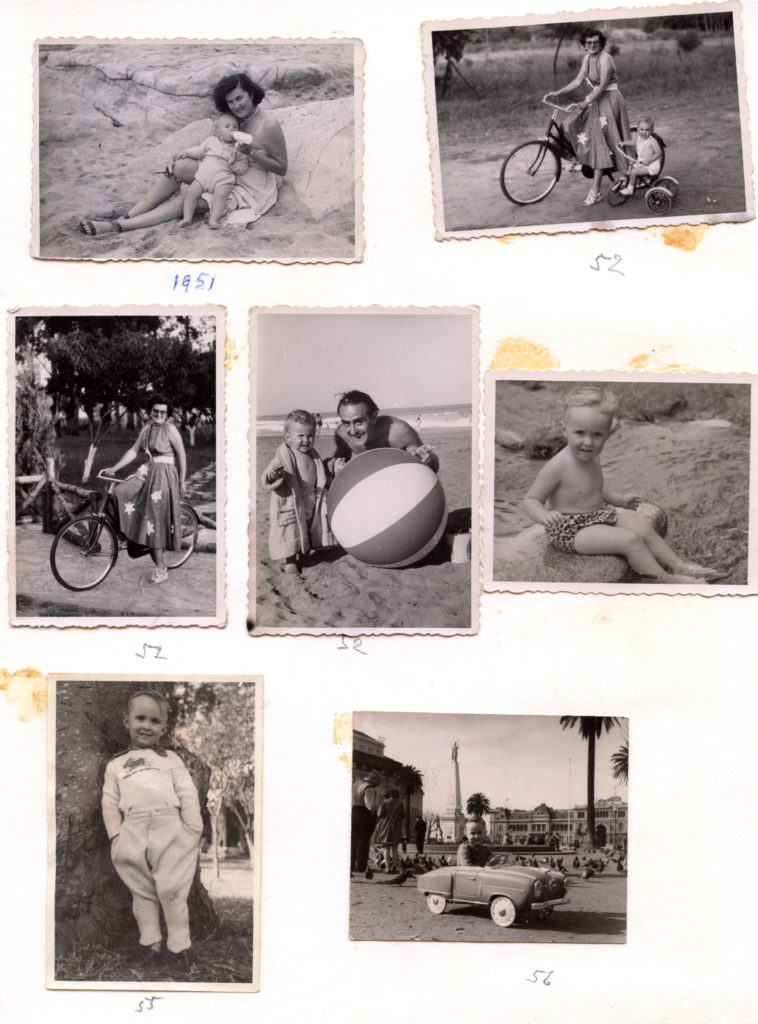

The first child was 2 months old when we came to Gresford. We had the child, before we went there in Sydney. He was born on November 18th, 1942. It was John, and we came to Gresford in January 1943. It was very hot there, shocking, the bush. Aviva was born on November 30th, 1944 in Sydney. Why in Sydney? Because I had a difficult confinement with John[4], and I did not want to have a second child. When I became pregnant, I went back to Sydney to see my gynecologist, and he said he will do an abortion to me, because he said it was very soon. He thought I should not have a child so soon. But Erich could not hear of that. On the contrary, it would be better for me to have the child quicker than to wait a few years. It was a terrible confinement. It was a brow presentation. So, it was a very difficult forceps delivery. I came to Sydney 3 weeks before the confinement, and I stayed with Mrs. Star. And then, 3 weeks after the confinement, I went back to Gresford.

We stayed in Gresford all together 5 years. In the meantime, the war was over, and he was in private practice then. We stayed on, but we decided to leave Gresford. When the news got around that we planned to leave, there was quite a big stir, and the people formed a committee, which tried to persuade us to stay. But we had made up our minds quite definitely by then.

Since we had made up our minds, they decided to give us a great farewell. The affair was in the way of a banquet and everybody, really everybody turned up and they made a presentation to us and even to the children. The children were also present, and we got a beautiful set of silver cutlery that I bought for the money.

What then followed was a disaster. It was a most peculiar arrangement between a Polish-Jewish doctor and Erich, who wanted a caretaker for his place. He was a very sick man, and he wanted somebody to mind his house and his practice, and take over when he did not feel well. It was a gentlemen’s agreement without gentlemen, but it did not work out. Erich was sitting in the living room, waiting till Dr. Franklin did not feel like seeing a patient and said: “You can take over now.” An impossible situation and it drove us mad. We looked around for something else, and we stayed there for about 9 months.

Then we went to Warragamba. It was a position that was advertised in the medical journal. He applied for it and he got it. That was in 1949,[5] and they needed a couple of doctors there. There were 2 doctors there, two nurses, and an ambulance. He got a house there, rent free, from the government. He had to take care there of the workers and their families for a fixed salary. That was already nearer to Sydney, and we could look around. We were there for 2½ years, until we found that practice in Auburn. It seemed to be interesting for us. We saw many things before, but unfortunately we did not have any money, and we had to borrow. Mr. Star used always to say he would help us, but every time we saw something and we went to him, he would look at the places and would inspect the water drains, which was from a builders point of view interesting, but for us the interesting point was whether we could make a living there. And he was not interested in that at all. So, we could see that it was useless to go and ask for any assistance from Mr. Star. We would never get anywhere.

So, when we finally found this place in Auburn, Erich went to Mr. Harris. He went to Mr. Harris to his business in town, and he told him that he had been looking for a place and had found one, but that he needed some money to buy it. And Mr. Harris did not ask anything at all, he did not ask how much, where, what, why, he went to the phone and rang his bank manager and said: “Look, my very good friend, Dr. Ziegler is coming to your place. You give him whatever he needs.” And that is how we got the money. We did not tell Mr. Star till after we bought it, because we were not interested in the drainage of the house. We could see that this was the right thing for us. It was within our means, and Mr. Harris made the only mistake: He lent us the money interest-free, which for us was a liability. We paid it back too fast. We deprived ourselves of everything. I could not have a washing machine, I had a fuel copper in the laundry, I did everything myself for years, with the children, with the practice, it was a real hardship. I don’t know how I managed. I had a difficult secretarial job.

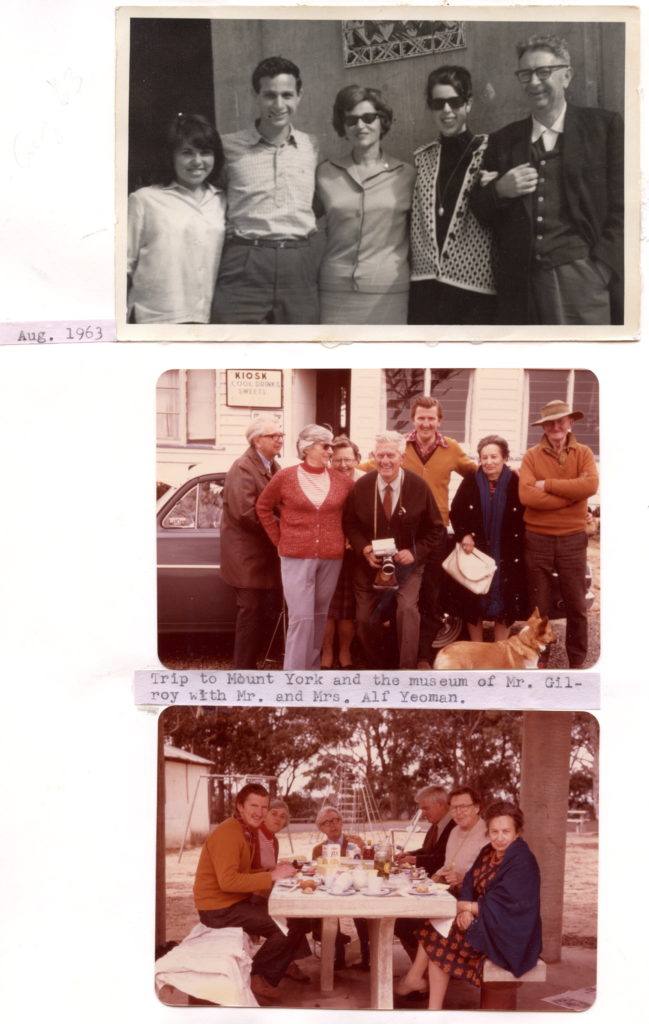

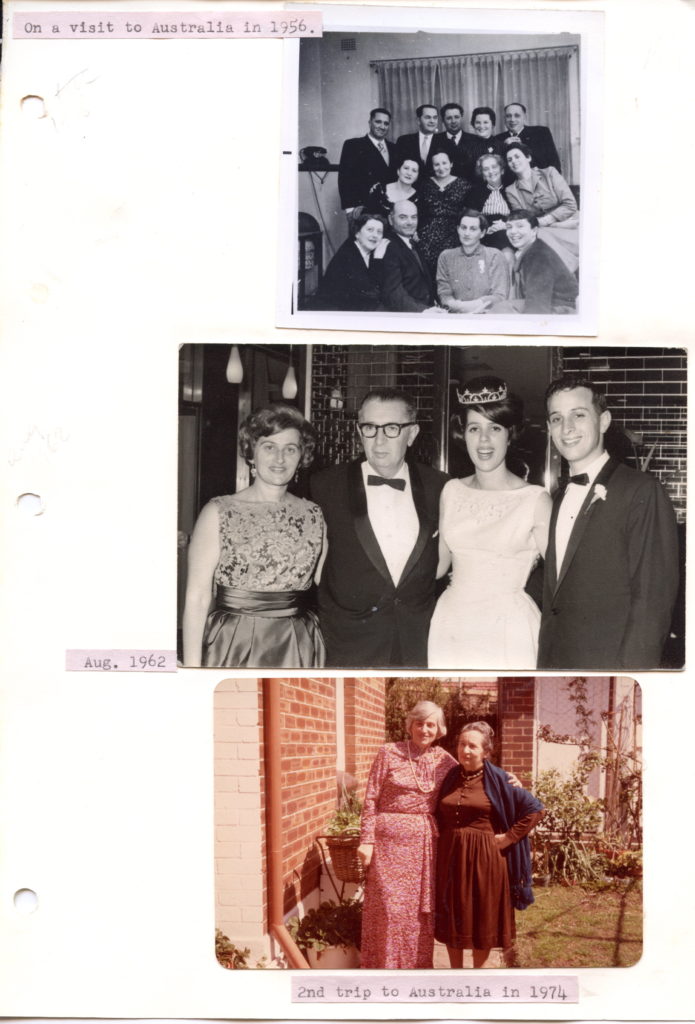

You came to visit us in July of 1956 to Auburn. The next year, Erich came to visit you in America. After he came back, he decided he had worked too hard. He did not work then that hard anymore. He took in a man as an assistant, while he was away, he liked him, he was good. He made an agreement with him behind my back. I had said to him: “Whatever you do, you should never give him a 50-50 partnership, make it 45-55.” He did not agree and he did it without my knowledge. The partnership paid rent for the use of the premises.

But it became too complicated, the place became too small, and Erich said that he will have to get another place for the surgery. But he liked staying there, he liked the place. He had moved so much, he did not like to move anymore, and I said that if any changes happened, we will move out and the practice will stay here. I stood my grant, until we moved. We bought the house in Strathfield. The doctor became a half partner, a 50-50 partner.

The coronary he had years before, about 12 years before, when John got his leaving-certificate, what we used to call matura or arbitur, with 17 years, and that was in 1959. Then he started to study medicine, and he was doing the final exams for his second year,[6] when Eric got his heart attack. And he recuperated nicely, and then continued with his office work.

The stroke he had in June of 1970, when the partner did a nasty thing to him. He had prepared another surgery for himself in his home, a few blocks away, and one day simply cancelled the agreement. This caused enormous excitement to Erich and caused the stroke. The doctor took then everything out of the office and left it almost empty.[7] Erich was for weeks unconscious in a kind of coma, incontinent. He was then moved to a hospital for rehabilitation, because clinically he was not on the danger list anymore. The partner took the furniture, the case histories, he took everything he possibly could.

About my grandparents I know very little, since they had died before I was born. My mother’s father was Bernhard Schick, and her mother’s name was Elizabeth, nee Eisner. My father’s name was Isador Schacherl, and my mother’s name was Else Schacherl, nee Schick. My sister is Fritzi and her husband’s name is Leo Zimmermann. They were married in 1934 in Vienna. My father was one of 5 children. My mother was also one of 5 children, 4 girls and 1 boy.

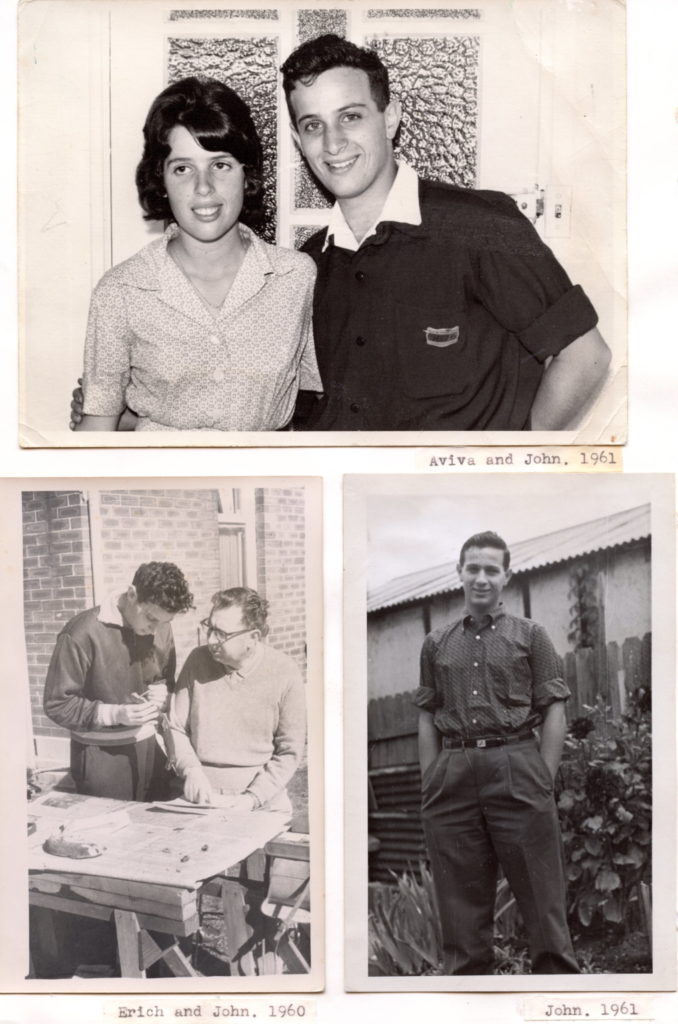

John graduated as an M.D. in 1965. He had 2 years of internship, then went to the Veterans Hospital for about one year[8]. Then John Penny asked him to join at the hematology clinic at St. Vincent’s Hospital. He started to become involved in immunology and he stayed for two years, and then he got the Fulbright Scholarship[9] and went to Boston. First he got the grant from Sydney, and the Harvard Foundation increased it for another year in Boston.

John got married on October 26th, 1969.[10] His wife’s name is Mary and her maiden name is Stein. Their first child was born on January 23rd, 1971. That is Debbie, and David was born on June 24th, 1972. Mary was 23 when she was married. Her parents names are Adek and Hela Stein. They came from Bialystok.[11]

Aviva was born on November 30th, 1944. She went to high school, then to a business college and then to a private college. Aviva got first a secretarial job with a very big firm, and she stayed there for 3 years, until she made her first trip overseas. Her last job is as an assistant producer at the ABC, Australian Broadcasting commission.

When we came to Australia, we had relatives here without knowing it. These were Claire and Hans Schiller, who arrived in Sydney a month before us. We met his brother by accident and immediately got in contact with them and also with Grete Schiller, and we have been since then always closely associated with them. When we finally found out that Walter Ziegler was alive in Prague, had survived the concentration camp and he needed to go somewhere, we helped him to come to Australia. We had very good connections then, and got a permit for him, and also for, his niece, the daughter of his sister Emmy Meisel. So, they both came to Australia also. After them Hugo Husserl came. And then Trude, Claire’s sister came from England. She was married early in her life in Vienna and she divorced this man, and went to England. She met there a man, Bert Spitzer. After this man had found out that his wife and child had perished in a concentration camp, this Mr. Bert Spitzer, who was from Czechoslovakia, and Trude got married. When he died suddenly of a coronary, she decided to leave everything behind, and come to Australia. She died last February cancer of the breast. Hugo had died in 1955.

[1] Correction: Norway

[2] Helsinki

[3] Actually Jacques who worked for Rothschild Bank

[4] 4 day labour

[5] Around mid-1948

[6] 3rd year actually, that would make it 1962.

[7] The files were handed over to him as a result of a court settlement.

[8] 2 years

[9] and grants from the College of Physicians and the Cancer Council.

[10] Actually 19th.

[11] Warsaw (Adek was born in Bialystok and his family moved to Warsaw when he was a child). His surname was Bulkowstein, shortened to Stein at the time of their naturalisation as Australian citizens.