1936

The year 1936 was for me a good year, not only because I became the father of a second child, but because before that I had made an important invention in the medical field, which made an enormous impression in almost all of Europe and beyond that area. It was a new treatment of the common cold, hay fever, sinusitis, chronic rhinitis and vasomotor rhinitis. It was in the form of an ointment, which contained a very small amount of a certain kind of snake venom and had to be rubbed into the skin of the forearm.

A company in Germany, Mack in Ulm in Bavaria, had put on the market an ointment under the name of Forapin, which contained bee venom, and claimed that it was very effective in rheumatic conditions when rubbed into the skin over the affected joints. I became interested and started to recommend it to patients.

Among them was a lady, who had severe sciatica, an inflammation of a sciatic nerve. This was an old patient of mine, who had all kinds of other medical problems. She had suffered for many years from vasomotor rhinitis, the main symptoms of which were severe attacks of sneezing and watery secretion from the nose, which usually started in the morning. Instead of handkerchiefs she had to use a bed sheet to combat the enormous secretion. These patients were usually under treatment by nose specialists. I had sent this patient once for treatment to a Dr. Weil, who had used cauterization of the nasal mucosa with an acid. This treatment had to be repeated many times. There was some improvement, but afterwards the condition continued as before.

For her new problem, the sciatica, she started with applications of the bee venom ointment and rubbed it in daily. She returned later to report that the bee venom ointment had not helped. Asked about her nose problem, she said that the sneezing attacks had ceased completely. I suspected that the bee venom may have had something to do with it.

I happened to have another patient who was also suffering from vasomotor rhinitis and I called him up and told him to go to a drugstore to buy a tube of that ointment Forapin and how to use it. He did it and a few days later told me that the sneezing attacks had ceased completely. This was exciting news for me. I started now to use it on other cases, on patients with common cold and hay fever, on cases with chronic sinusitis etc., in all cases with amazing results.

Since bee venom is very difficult to obtain and therefore very expensive, I switched to snake venom, since snake venom is in many aspects similar to bee venom and much less expensive. I had to try out different kinds of snake venom till I found the right one.

Before publishing my invention, I made a contract with a big company, the Serum Institute of the Austrian Government, securing for me good royalties. On June 19, 1936, I spoke in the Gesellaschaft der Aerzte (Society of physicians) about my invention. It made a great impression and the next day all the newspapers reported about it under big headlines on the first page. The next days and weeks were like a storm, as the telephone did not stop ringing and enormous amounts of mail started to come in. Newspapers reported it all over Europe and I have a collection of newspaper clippings, all together 140.

I published two articles in medical journals, one in 1936 and the other one in 1937. The name of the ointment was Viperin, and this name was patented in many countries, but in some countries the Serum Institute came too late: in Germany for instance by a few hours, and there the preparation had to be registered under the name Serpin; in Tchechoslovakia under that name; in France under the name Viperol; but in all other countries under the name Viperin. A few days after my announcement of the invention, a photographer of the Associated Press came and took 2 pictures of me, and other photographers came too, and my picture appeared in many newspapers. I should also mention that my brother Carl became the sole representative for Romania for this medicine under the name Viperin.

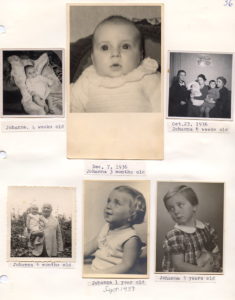

Now back to Hedy. She gave birth on September 7, 1936, at 6 P.M. to a very beautiful girl with blue eyes and blond hair, a splendid specimen. She received the name Johanna, but we called her Hannerl. In the afternoon before she was born, Hedy was still at home and we had a visitor, Ernst Husserl, a cousin, and Hedy invited him for coffee. But soon labor pains started and I had to rush her to the hospital. About an hour later, Johanna made her entrance into this world. Unnecessary to say that the whole family was happy about that event. My mother took care of Johanna at night, both occupying Francis’s room. I remember how successful my mother was, when the baby woke up and cried, in calming her down by singing for her in a low voice, sometimes changing diapers if necessary. There came a lot of visitors in the next few days and weeks, a constant coming and going. And there was more and more excitement about my invention of Viperin.

One day I was interviewed by a reporter of the newspaper Der Morgen, and a few days later, on October 5, 1936, a big article appeared about me in that paper. There was great excitement in the Serum Institute about that article, and it was not clear to me what the reason for the excitement was. It became clear soon, when I saw that the director of the institute, Dr. Csonka, and the chief of the department of serology, Dr. Kovacs, both Hungarians, had tried to usurp for themselves the merit of having invented the medicine by putting their names right under the name Viperin on the pamphlets that explained how to use the ointment, which were in every package wrapped around the tube. My name also appeared in that pamphlet further down, describing my “observations with that ointment.” They probably had planned a newspaper article themselves, putting their names in front as the inventors of that treatment. Now they could not do that anymore. Everybody knew anyway that I was the inventor, and I let things rest where they were.

What these two people in reality had done was change the amount of snake venom in accordance with information, which I had given them. That was all. In the beginning, before putting the preparation on the market, they needed information from me about the amount of snake venom which was most effective. For that purpose they gave me different batches of ointment with numbers, without telling me the exact amount in units of snake venom in each of the batches. I tried them out on my patients in my office, and could finally tell which batch was most effective. Now they could go to work and produce the ointment. They kept the amount of snake venom per gram of ointment as a secret to themselves, which was, of course, very unfair. Years later, when I was in Cuba, I found it out myself, by experimenting with mice, that one gram of ointment contained 20 mouse units of snake venom.

I should mention here that I had made many enemies with my invention, which I should have anticipated. Almost all specialists in the field of rhinology (nose specialists) were opposed to this method of treatment right from the beginning, before they even had a chance to try it, and were ridiculing me. But, on the other hand, there appeared later a number of publications in medical journals by prominent people in the field of rhinology describing excellent results with that ointment. It was distributed in many countries in Europe and I began to receive nice royalties.

This is a copy of a leaflet which was enclosed in every package of the ointment, sold in drugstores, giving instructions to patients how to use the ointment. I do not have anymore an original pamphlet, have only this photography to show it. Also, below, the carton, which contained the tube.

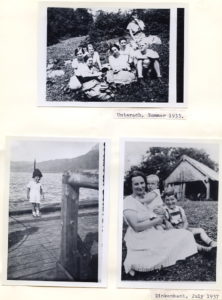

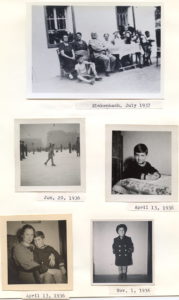

Looking at the photo album, I see in one picture my mother, Hedy’s mother, Francis, and Hedy, holding Johanna in her lap. Other pictures showed Johanna, taken at different times, developing into a most beautiful child. One picture showed Francis on skis at the beginning of 1937, when I went with him to the Semmering in the Alps south of Vienna.

[Click here to read additional photo notes by Francis.]

At about that time [1937], or perhaps half a year earlier, we thought that it was time that Francis started with piano lessons. We found a very fine teacher for him, young and pretty, a Miss Feucht, and he showed in the beginning much interest and ambition. But it did not last long, especially because he had to practice and that he did not like. It was a pity, because he was so talented and had a good ear. I had decided to take myself also lessons with that same teacher and enjoyed it very much. The first thing I had to do was to practice scales and the diminished septaccord in major and in minor. I had never heard about it before, but I liked it and did it quite veil. Then she started with more difficult pieces, the Chopin Raindrop prelude and some others, much more difficult ones. We stopped with Francis’s lessons because he refused to practice, but I continued for a while. Miss Feucht became ill and I was her doctor and found out very soon that she had tuberculosis of the upper lobe of one lung. What became of her, I don’t know.

I had said once already that my musical education was very sporadic. I may have mentioned that as a little boy I had as a teacher for a few years, a Mrs. Tomovici. She was a little hard of hearing, but in general a good teacher. Afterwards I played myself without a teacher and learned to play many pieces by heart. Before the outbreak of World War I, I took lessons with a fine teacher, Mr. Kraemer, at the Conservatory for about a year. At that time I was quite skilled in playing popular music, especially operetta music, which were popular then, of Lehar, Pall, Kalman, Oscar Strauss, Eysler, Granichstaetten, Offenbach, Stolz, etc., and played them often for young people for dance. For one year after the war, I took again lessons with a Mr. Kostelecki, who was for many years conductor at the theatre, but now a very old man with severe arthritis of the hands. I learned from him also a lot.

I should add here that my interest in music was always very great and played an important role in my life. I was a frequent theatre-goer, also went to many, many concerts during my life, subscribed in the Metropolitan Opera for many years up till now. As a young fellow, I had heard great virtuosos in Czernowitz already before the First World War, like Arthur Rubinstein, Arthur Schnabel, Jan Paderewski, Wilhelm Backhaus, Pablo Casals, Moritz Rosenthal, Fritz Kreisler, Bronislaw Hubermann, Eugene Ysaÿe, and many others. About some mentioned, I am not sure whether I heard them in Czernowitz or later on in Vienna. Ysaÿe, a Belgian, was the greatest violinist of his time.

Music fascinates me to such an extent that I cannot talk while it is being played, nor answer any questions, except for one word or two, and I get into a rage when somebody wants to have a conversation with me while fine music is being played. I cannot bring out a word while I am playing myself, and am almost unable to sing the melody or the text of songs while playing myself. When I read or write and music is being played in the next room, I have to stop reading or writing. This is a handicap that I am unable to overcome. Fine, very low-keyed background music is an exception, but bad music, like rock and roll, does not have the same effect and that goes also for so-called atonal music. It took me a long time to accept and listen to music by Schoenberg, Bartok, Stravinski, or Shostakowicz, which I slowly learned to appreciate, till I included them in the list of great composers, but they still don’t fascinate me.

I should mention here also that I like to sing, and as a young doctor in Vienna, I was a member of a doctor’s glee club, and we often gave concerts. We were a group of about 25 doctors, and many of them had good voices. I usually sang the baritone parts, but my voice had a wide range up to the middle of tenor and down to the middle of bass. I enjoyed very much the many rehearsals and then the singing in the concerts, which contained often in the program very humorous parts. I remember that we once sang the choral of the prisoners of Beethoven’s Fidelio, which was a great success. I often sang to the [piano] accompaniment of Francis songs by Schubert and others, and it was always fun. One of my favorites is the song “The Two Grenadiers” by Robert Schumann, with words by Heinrich Heine. Another favorite is the song “Die Uhr” (The Watch) by Carl Loewe, with words by Gabriel Seidl.