1928

One more important interruption of my hospital work was our wedding on March 4, 1928. We had planned it long before and had hoped to take over a practice from a doctor, who had a position as rayons-physician of the Arbeiter-Krankenkasse, which means Workmen’s Health Insurance or something like that, the same position which my father-in-law had had for 36 years. Such an opportunity arrived when Dr. Krips had died. We spoke to his widow and she promised that she would help me to get her husband’s position. She offered us the entire lower floor, where he had his office in the 19th district at Ferdinand von Saar Platz, for rent. She also promised us to get us some of his patients in the meantime.

The office was poorly equipped with very old furniture. She asked quite a high rent, 200 Austrian Schillings, and without much hesitation we accepted the offer. We thought it was an excellent opportunity. It was in reality a very wrong step, but in many respects good. We had a home and could get married. Carl supported me and we could do it.

The wedding took place in the temple in the Seitenstettengasse the 1st district, officiated by Rabbi Dr. Taglicht. The wedding feast took place in the home of Hedy’s parents, where many members of her family were gathered for a fine celebration and meal. A great many of Hedy’s relatives were there, many from faraway places in Tchechoslovakia, but most of them from Vienna. From my family some who lived in Vienna were there, out many came from far away, from Czernowitz like my mother, Carl with his wife Lotte and his mother-in-law Clara Ohrlaender (whose husband had died shortly before on July 1, 1927 at the age of 59). Everything was well planned and prepared. It was amazing, how my mother-in-law, with the help of Lisa, had stored away beds and other furniture, so that 4 big rooms could be used for the enormous number of guests.

It was a beautiful affair, fine and plentiful food and drinks, many toasts. Carl sang a few songs, and everybody was happy. The guests stayed till late at night, but Hedy and I left earlier and went to our new apartment on Ferdinand von Saarplatz for a short night’s rest, and got up very early to get to the train station for our well-prepared honeymoon trip to Venice. We stayed in the hotel Marconi near the Ponte Rialto on the Canal Grande. We visited almost all the art galleries, many palaces, churches, also the islands of San Giorgio Maggiore, Murano, and Burano, including the glass factories, and returned home after 10 or 12 days. It was a wonderful trip. I continued working at the hospital, at the department of gynecology and obstetrics.

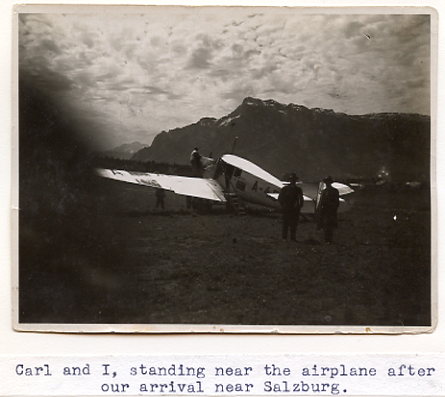

Once Carl arrived from Czernowitz. We were just two months married, and he asked me to accompany him on an airplane flight to Salzburg and from there to Berchtesgaden in Bavaria by car. Airplanes were at that time not much used and flights regarded as dangerous. But I agreed, although Hedy was not very happy about it. Only the two of us were in the airplane. It was an open plane, no floor, only metal rods instead, on which our two valises rested. When we looked down between the metal rods, it gave us the jitters. But everything went well and we landed in Salzburg. There we rented a car, which took us to Berchtes garden, where Carl had to sign a contract with a Mrs. Sedlitzky, who had the patent for a mineral salt formula, Darkauer Jod Salt, which was used for baths. Carl had then the right to produce it for all of Romania. We made a short visit to the Koenigsee, but it was already late in the day and we could not see much, only the steep mountains on both sides of the lake. Back to Salzburg and then by train to Vienna and Carl to Czernowitz. Hedy was happy to see me alive.

In June of 1928, my mother-in-law had the misfortune to get a severe gallbladder attack. She’d had bad gallbladder attacks before already, but this one was very serious,with jaundice and high fever. Professor Schnitzler was called and he had her immediately transferred to the Sanatorium Loew, the biggest and best in Vienna for an operation, which he performed the same day. It was a phlegmone of the gallbladder, which was enormously enlarged and contained a great number of stones, some of them larger than cherries. She recuperated nicely. Antibiotics were not known then and she had in the beginning for a few days fever and a drain and a long gauze tampon in the wound, which professor Schnitzler, who came twice a day to visit her, removed gradually. Altogether, she was 18 days in bed.

I visited her daily and became acquainted with the sanatorium doctors. One of them, a Dr. Fisch, suggested that I could get a position as a sanatorium doctor, or as they called it house doctor, and could make a nice amount of money. The sanatorium hired every year for the summer months a doctor to substitute for the 5 or 6 regular house doctors during their vacations. Dr. Fisch intervened on my behalf and I was accepted and could start almost immediately on July 1st. I was very happy and so was Hedy.

Very soon I started to bring nice amounts of money home, which the different surgeons, whom I had assisted at the operations, had put on the patients’ bills for me, also when I did the anesthesia’s. Most of the patients were very rich people, many were aristocrats, and a fee of 150 or 200 Schillings for me was not hurting them. Often patients handed me an envelope with money when they left. I remember that on one day I brought exactly 1000 Schillings home. My work there terminated after 4 months on October 31st, 1928, and I had accumulated a nice amount of money. The work was not difficult, but I had to stay there every 3 or 4 days at night and that was the bad part of it, since I hardly got a chance to sleep.

On the other hand, it was very interesting work, since I became acquainted with almost all the professors of the University, among them many famous people, seeing them operate, doing anesthesia’s or assisting them at operations, and discussing their cases with them. There were fields of medicine in which I had not had a chance before to work, like urology, orthopedic surgery, neurology, ophthalmology. There were also innumerable tonsillectomies, nose operations, larynx operations, and mastoid operations, which I had also not seen before.

I had to take care of about 10 patients in 10 rooms in an older part of the building, which was called “the burg,” which meant in case of operations the complete aftercare. Some surgeons visited their patients once a day for a few minutes, gave their orders and left. But some surgeons were very negligent and came only every 3 or 4 days. In these cases it was really I who had to take care of the patients, prescribing medications, changing bandages, etc. When I had night service, I had to take care of all the patients in the sanatorium, which was an enormous job, with much responsibility. There were often complications and emergencies, where I had to intervene, and the responsibility was great, when I could not reach the doctor, to whom the patient belonged, by phone. All that, practicing in the way I described, was very valuable for my medical education and a good preparation for my future practice. When the 4 months were over, I returned to my hospital to resume my work as Secundararzt.

Regarding the hospital work in the departments of internal medicine, I should also mention that the doctors had to do almost all the laboratory work themselves, each doctor for the patients who were under his care. That meant examinations of urine, blood, sputum, and stool, since there was not a laboratory, as we have it now, to do all these examinations for the whole hospital. Only very difficult examinations were done in the pathological department, like blood or urine cultures for bacteria or Wassermann tests for syphilis, Vidal reactions for typhoid fever, examinations of pus, etc. But other examinations were done by us doctors, examinations of blood for urea and bipod sugar, also for the amount of hemoglobin, blood cell counts including differential counts, stool examinations for parasites, sputum examinations for tubercle bacilli, etc. The department of internal medicine had to do these examinations also for the other departments, for the departments of surgery, gynecology and obstetrics, dermatology, etc., whenever they asked for it. That kind of work kept us doctors quite busy. We learned how to do it and that was very valuable later, when we went into private practice.

I want to add here also that I had done quite a few autopsies while working under professor Carl Sternberg in the department of pathology. I had the misfortune of infecting my left thumb with tuberculosis when performing an autopsy on a girl with tuberculosis. It was only a slight scratch, and when I looked for it after the autopsy to take care of it, I could not find the spot anymore. But about 14 days later the infection showed up, and although it was at first cauterized and then operated on, it showed up again, and when the infection started to look bad, an assistant of professor Schnitzler did finally a more radical job by removing a piece of skin with surrounding normal tissue, and suturing the defect, and that was the end of it. Such infections of the hands were not rare among pathologists.

The apartment, which we had rented on Ferdinand von Saarplatz, was, as we later found out, the wrong place for us. We should have inquired about it before we had rented it. We would have found out that Dr. Krips was involved in a great scandal and was dismissed from the Arbeiter-Krankenkasse. He was caught by the husband of a patient, hidden behind a curtain, while making amorous propositions to her. He was beaten up by him and then denounced to the Krankenkasse and the police. He was the father of the famous conductor Josef Krips, well known at that time especially in Germany, later all over the world. The story about the scandal was in all the newspapers, but we had not known about it. Shortly afterwards, Dr. Krips committed suicide by shooting himself, and shortly afterwards we had moved into that apartment. The position of a physician for that rayon was offered in a medical journal, and I had sent in my application too, but the position was given to another doctor.

Besides that, the apartment was very bad in many respects. There was no running water in the office and only one water outlet for the whole apartment in the hallway. There was no real bathroom to take a shower, only a toilet. For heating in winter there was one big metal stove to be heated with coal, in one room. It was a disaster, and we knew that we would not stay there long. We were badly misled by Mrs. Krips.

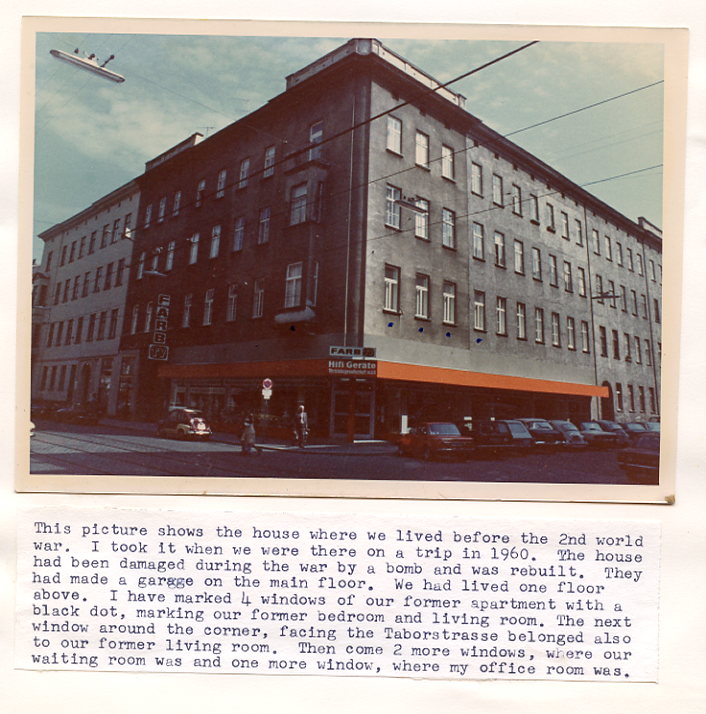

We started to look for an apartment in the 2nd district, and it took a long time till we found the right place in the spring of 1929.

Hedy and I were once walking through the Taborstrasse, not far from where the parents lived, and at the corner of Darwingasse, I looked up at the windows on the second floor, one floor above the ground floor, and told Hedy that that would be the right place for us, I went to the house steward for information and found out the name of the tenant of that apartment, was Mr. Hochstimm, and also that he was in a very poor financial situation. I found his name in the telephone directory, called him up, and asked him, whether he would consider moving out of the apartment. I told him that I was interested in renting it, and that I would help him with money to rent another apartment. He said that he was willing to consider it. Hedy and I went there on one of the next days to take a look at the apartment. It consisted of 3 large rooms and one smaller room, a so-called cabinet, since it had only one window, an entrance hall, kitchen, a room for a maid, and a toilet. We found the apartment excellent for our purpose, after certain extensive construction work. After we got the consent of the owner of the building, we signed a contract with Mr. Hochstimm. We agreed that we would get the apartment on May 15, 1929, against payment by us of the amount of 3,500 Schillings, which was a nice amount of money in those days.

The construction work began immediately. Since the apartment had no running water, it had to be brought in from the hallway. For the lying of pipes, the floor of the entrance hall, the kitchen, and the room for the maid had to be removed. It was planned to partition the room for the maid, so that a bathroom could be built with a bathtub, wash basin, and a heater, heated by gas. We got a modern kitchen with running cold and hot water, and a wash basin with cold and hot water in the adjoining cabinet, which became my office. For heating of the apartment in winter a big ceramic stove was constructed, which was put into the wall in such a way that half of the stove was in the living room and the other half in our bedroom. It was a beautiful stove, and was to be fired with big logs of wood. Then came electrical work, and finally painting.

All that required a lot of money. We had accumulated some, but a neighbor of my in-laws, without having been approached, offered us a loan, which easily covered these expenses and also expenses for furniture and office equipment. We paid it back in regular monthly rates, and had the whole loan repaid in the course of 2 or 3 years. It took a long time, till we had our furniture, made to order, and could finally move into the apartment.

In the meantime, I had worked in the hospital, and one day I received a call from the Sanatorium Loew and was asked, whether I wanted to work there again during the summer. I wanted to, and I started on June 10 and worked there till October 6, altogether about 4 months, and it was again a good opportunity to earn a nice amount of money, which we could use very well. Our biggest worry was that I should get the job as rayons-physician, which my father-in-law had had for 36 years. There were many young doctors in Vienna who were waiting to get such a job, and we knew that good connections, which we called “protection,” was necessary to get it, and that we did not have. At that time the head of the Austrian government, the chancellor, was a churchman, Konsignore Ignaz Seipel, who was a strict clericalist and anti-socialist, and for me as a Jew the chances were not good. But I had enormous luck, and I have to tell an interesting story in detail.

It so happened that one of the patients in my department in the “burg” was a man who was minister, or what we call here secretary of the Ministerium for Health and Social Welfare, a Mr. Aladar von Duda. He was operated on by professor Schnitzler—it was an abdominal operation—and everything seemed to go well. He was transferred to my department a few days after the operation. But after a few days a serious complication started, a paralysis of the intestines, which we call ileus. All kinds of medicines, injections of Physostigmin, etc., did not help, nor did repeated enemas and high clysmas. By auscultation of the abdomen there was no noise audible. The abdomen was enormously swollen, and the patient had gradually gone into a kind of stupor. He did not eat nor drink anything, of course.

That went on for days and professor Schnitzler was desperate, and so was Dr. Schawerda, who was the doctor who had recommended professor Schnitzler for the operation. On the day the patient was transferred to my department, professor Schnitzler came early in the morning and ordered another Physostigmin injection, and said that if it does not help, he would have to operate in the afternoon again and do a colostomy, which means an operation opening the abdomen and the colon. This would probably not have helped either.

This was a moment, where I could recommend something. I told professor Schnitzler that I had seen a good result in a case of paralytic ileus in the Wiedener Krankenhaus in the department of professor Halban, where an intravenous injection of Pituitrin, mixed with glucose, had an immediate effect in restoring the peristaltic activity of the intestines. Professor Sennitzler seemed to be very happy, and asked me to give the injection to the patient and left. While I prepared the injection, Dr. Schawerda told me that he would give the injection to the patient. I agreed, but said that it had to be given very slowly, since it is a very powerful drug. Dr. Schawerda said then, “No, it is better you do it.” I succeeded in scaring him away.

There was the wife of the patient in the room, also his brother, a retired high officer of the army, and Dr.Schawerda. I asked the nurse to put the patient on a bedpan and they all laughed. He had not had a bowel movement for 8 to 10 days. Anyway, the patient was put on a bedpan and I started the injection. At first I injected a small amount, about half of one cc and then waited a while. Soon we heard a gurgling noise in his abdomen, and the brother of the patient said, “What wonderful music!” Then I injected another half cc and again we heard that gurgling noise. Then a whole cc, and the patient started to press and evacuated gas and a small amount of stool.

I went ahead now with the injection in shorter intervals, and the patient began to evacuate large amounts of stool. At the end, the bedpan was filled to the rim. There was jubilation in the room and everybody was happy. The patient started to talk normally, his abdomen had collapsed to normal size and he was all smiles. He had not eaten for days, and now he had a small lunch, since he had become hungry. Professor Schnitzler was especially happy, when he came in the afternoon. The next day, the patient was out of bed, and one or two days later he left for home, completely cured. But before he left, he said to me, “Dr. Mechner, you have saved my life, and I will be grateful to you as long as I live. I wished I could do something for you.” For that I had waited, and I told him, “I think I know, what you could do for me.” I told him about the position of my father-in-law, which I would like to get, and the rest of the story. I don’t remember the exact words of his answer, but it was very promising and he said I should call when my father-in-law will be ready to retire. I was now really happy.

But I had also another iron in the fire. I was taking care of another patient, a Mr. Kunz, who happened to be in a very high position in the Arbeiterkrankenkasse. He was “Obmann des Ueberwachungsausschusses” (chairman of the superintendence committee). I was often sitting in his room and talking to him about my problem and my worries about my future. Before he left, he told me that he would do all he could for me. I felt that I had hit the jackpot by working in that sanatorium.