Chapter 57. The Trip to La Bernerie

As our three car caravan headed south, we passed through a series of bombed out towns, some of them with all the houses razed to the ground and not a single roof visible. One thing that impressed all of us was that each town’s cathedral remained standing and almost intact, even when everything around it had been leveled. “Those bombers must have had really good aim,” Lisa commented.

In one of the leveled towns through which we passed, M. Roi stopped our caravan so we could get out and stretch our legs a bit.

“I think this used to be one of my banks,” he said, pointing to one of the big piles of rubble. He walked over to it, scratched around in the rubble with his hands, and picked up a torn scrap of paper.

“My money!” he said wistfully as he held up the scrap for all to see. Everybody laughed. He was hilarious.

We snacked on food brought along for the trip. I was shocked and disgusted to see M. Roi swallow a raw egg straight from its shell, in one big gulp. He urged Lisa to try it, too, and to my amazement she did.

When passing through Rouen, we stopped in the town square where Jeanne d’Arc was burned at the stake as a witch. I had always been fascinated by the story of Jeanne d’Arc and her gutsiness in leading an army against France’s occupiers. I sometimes fantasized that a present-day Jeanne d’Arc would appear and chase out the Germans. As I stood there, awestruck, I wondered whether being at the actual site of her fiery death increased my empathy for what it must have felt like to be burned alive.

Chapter 58. Our Stopover in St. Malo

By sunset we reached St. Malo, the town across from the island of Mont St. Michel. I was awed by the sight of Mont St. Michel. I had heard that at low tide there was quicksand between the shore and the island, and that people were sometimes swallowed up by the quicksand as they tried to make it across.

In St. Malo we saw another example of M. Roi’s unconventional approach to things. He wanted us all to spend the night in St. Malo, but, driving from one hotel to the next for about half an hour, he was unable to find accommodations for ten people. He eventually stopped in front of a commercial building and went inside while the rest of us waited in the cars. After a while he came back out smiling.

“All set,” he said with a triumphant smile. “We’re spending the night here.” Lisa told me later that M. Roi had, on the spot, rented the entire building for a bargain price.

The rooms looked like converted offices into which cots and mattresses had been moved. Lisa seemed annoyed with me when I asked her the next morning why she and Baer had to share a room when everybody else had their own rooms.

“We also slept in separate rooms,” she responded angrily. “Get that idea completely out of your head.”

I was sure that they had shared a room, but given how sensitive she was about the subject, I decided to drop it.

Chapter 59. Temporary Sanctuary

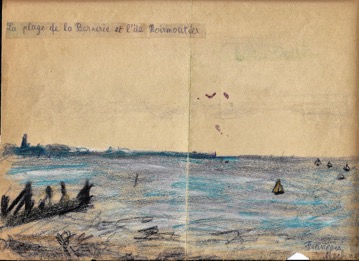

We reached La Bernerie that evening. It was a small, rugged fishing village on the coast of Bretagne, surrounded by large expanses of vineyards. Visible in the distance, across several kilometers of ocean, was the Île de Noirmoutier. We drove through the village and continued south for an additional two or three kilometers, to our final destination—M. Roi’s three seashore vacation houses. They were about thirty meters apart, with trees, hedges, and tall reeds separating them. Between each house and the beach was a vegetable garden about twenty meters in length, and each garden had its own flight of stone steps leading down to the wild and rugged beach.

Lisa, Baer, and I were assigned the house on the left—a two-room cabin facing the ocean. At the end of its vegetable garden, near the stone steps, stood an old neglected gazebo. The Roi family had the biggest house, the one in the middle. The three Polish sisters got the house on the right.

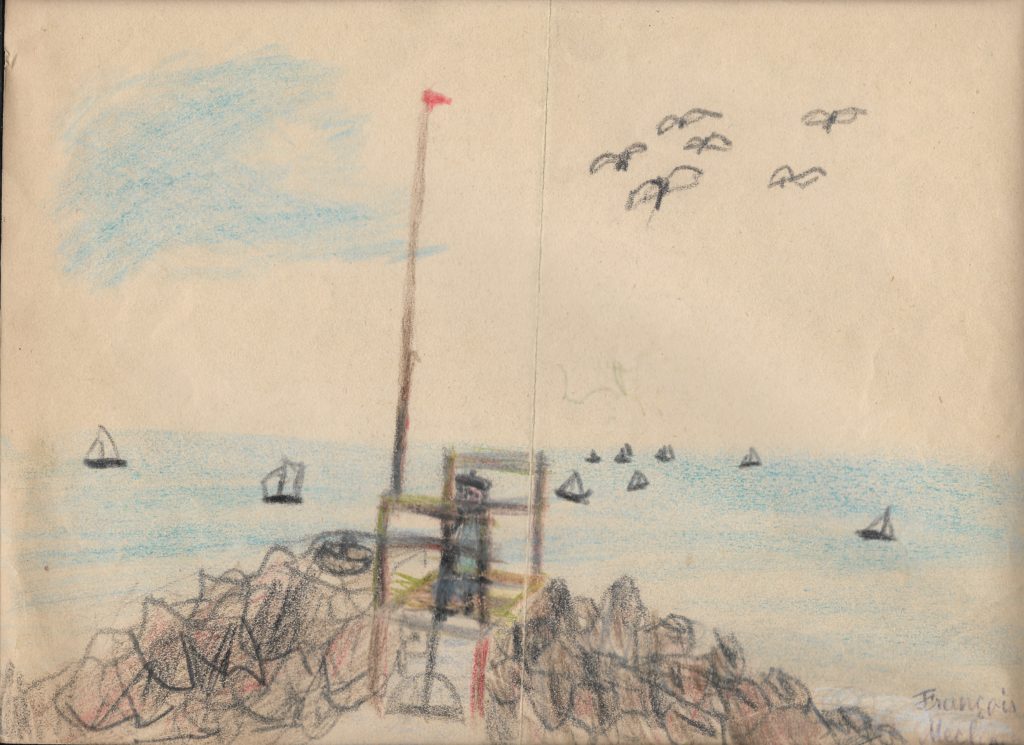

M. Roi told us that the Germans had not yet established a presence in La Bernerie and that we would be fairly safe. They wouldn’t find us, he said, provided we were very discreet, never went into town, and generally made ourselves inconspicuous. M. Roi’s son Jean would go into town regularly to get milk, butter, and sugar, but the rest of our group would stay as invisible as possible. The beaches of La Bernerie were rugged and wild. Dark seaweed and mussels covered jagged, algae covered rocks, and the sand was mixed with dried seaweed. The ocean had carved some of the rocks into weird shapes, and many had deep crevices in which crabs and other sea animals lived. Two long jetty-like walls made from piles of boulders formed a big triangle with the beach. In the meter-wide gap where the jetty walls would have met, about one hundred meters from the beach, was an écluse (sluice) across which local fishermen placed a net to trap fish on a large scale when the water rushed out through the gap as the high tide receded.

It was exciting to explore this new environment and I was relieved to know that we were safe from the Germans for the time being. But I also sensed that the price of this safety would be ever more isolation and separation from my family. How long would we have to stay here? Months? Years? Nobody could tell me. There clearly was no place to go from here, no next destination. For the first time, I contemplated the depress¬ing possibility that I would never see my family again.

Chapter 60. Lonely Activities and Houses for Cats

It was mid-September and the weather was still beautiful. I typically got up in the morning, had breakfast, and spent the rest of the day in long solitary wanderings around the beaches and fields. Almost daily, I swam far out into the ocean, as I had done in Le Touquet-Paris-Plage, to test the limits of my endurance under highly motivating conditions. I also spent hours on end jumping from rock to rock on the stonewalls of the jetties.

On the beach in front of our houses lived some wild cats. If I came within five yards of them, they would run away. Nonetheless, I appointed myself their provider and caretaker. I built them an elaborate apartment complex out of large pieces of wood that I found on the beach. The house I built had a complicated network of entrances, internal platforms, and passageways, fully furnished with straw and bits of cloth. What a thrill I experienced when the cats actually started to use it!

Feeding them was more problematical. Day after day, I examined every piece of reed I could find on the beach in the hope of finding that elusive piece of bamboo suitable for making a bow. I still believed that reeds were the same as bamboo. My plan was to use the bow to shoot birds to feed to the cats.

I also pursued another project. M. Roi had told me that you can make a flute out of the bark of a willow tree by finding a very straight segment of a willow branch, tapping the bark loose, and then pushing out the wood so as to leave an intact hull of bark that could then be made into a flute. I imagined that if I could make such a flute I would be able to play on it the Viennese songs I kept singing to myself.

Many willow trees grew along the banks of the streams that irrigated the vineyards. Armed with my cherished pocket knife, I spent weeks wandering through the fields looking for straight willow branches, cutting them off, and tapping on them. I never did succeed in making a flute.

Chapter 61. Alienations

My life in La Bernerie had no structure. No one seemed to care what I did. I had nothing new to read as I had already memorized the seven books I owned; my desire to draw had diminished; and the abandoned cats didn’t show much appreciation for my efforts on their behalf. I became increasingly depressed, and, as time went by, felt more and more discouraged about the prospect of ever seeing my family again.

My presence in the small two-room cabin that Lisa, Baer, and I shared obviously interfered with Baer and Lisa’s privacy. The problem was aggravated by Lisa’s persistent efforts to maintain the fiction that she and Baer slept in separate beds. Baer seemed to resent me, and our relationship was deteriorating. I once heard Lisa criticize him for the way he spoke to me. Once Baer even smacked me—the first time in my life that I was smacked by an adult. Lisa warned him never to do it again, but after that I was afraid of Baer and tried to avoid him.

Lisa, caught in the middle between Baer and me, began to distance from me a bit, or so I felt. I was careful not to make demands on her, for fear of becoming even more of a problem than I already was. So I made myself as scarce as possible.

Since we were supposed to be in hiding, I was told not to socialize with any local children I might run into. One day, however, a local boy wandered onto our beach front. I was given permission to play with him as long as I did not leave our premises with him. He was a bit older than I and not too bright. We spent time in my gazebo talking, reading my books, and drawing with my hard wax crayons. After a few sessions of that, I discovered to my great consternation that one of my books and some wax crayons were missing. I knew that he had taken them, but when I confronted him, he denied it. On Lisa’s advice, I sadly decided not to play with him anymore.

Chapter 62. M. Roi to the Rescue

M. Roi must have noticed my lack of focused activity.

“François,” he said to me one day, “I need you to make bundles of kindling for the stove and fireplace.”

He went on to specify in meticulous detail how to make those bundles. They had to be made from thin twigs about twenty centimeters long, and the diameter of each bundle had to be about five centimeters. Each bundle had to be neatly tied together with a piece of grass. Mr. Roi made such a bundle to serve as the model. I immediately threw myself into the task of fabricating such bundles. M. Roi’s high standards meshed perfectly with my own perfectionistic streak, and he gave me ample feedback. I enjoyed meeting and exceeding his standards, and made hundreds of perfect packets, many more than we could ever use up in an entire year. I stacked the bundles neatly along the hedge between our two houses and took pride in making the pile grow.

M. Roi, who was a superb chef, often invited us to dinner at his house. Not wanting this to be too one sided, he suggested various ways in which I could contribute to our sustenance, which consisted mainly of what we could grow in our gardens, or catch.

At first he assigned me the task of tending the vegetable gardens, in which we grew mostly lettuce, parsley, and scallions, and he showed me some basic farming techniques. One day after a big rain, he gave me a pail and told me to go out and collect all the snails I could find. I filled several buckets with more snails than the ten of us could eat in one meal. M. Roi fasted the snails for two days by locking them in a bathroom, to let them empty themselves out. Then he boiled them and took them out of their shells. He stuffed the empty shells with a mix of butter, garlic, and parsley, and then put the snails back into their shells for a final broiling. Yum. The meal at which we ate them was extraordinary, and M. Roi received ample compliments for his culinary skill.

Chapter 63. We Become Fishermen

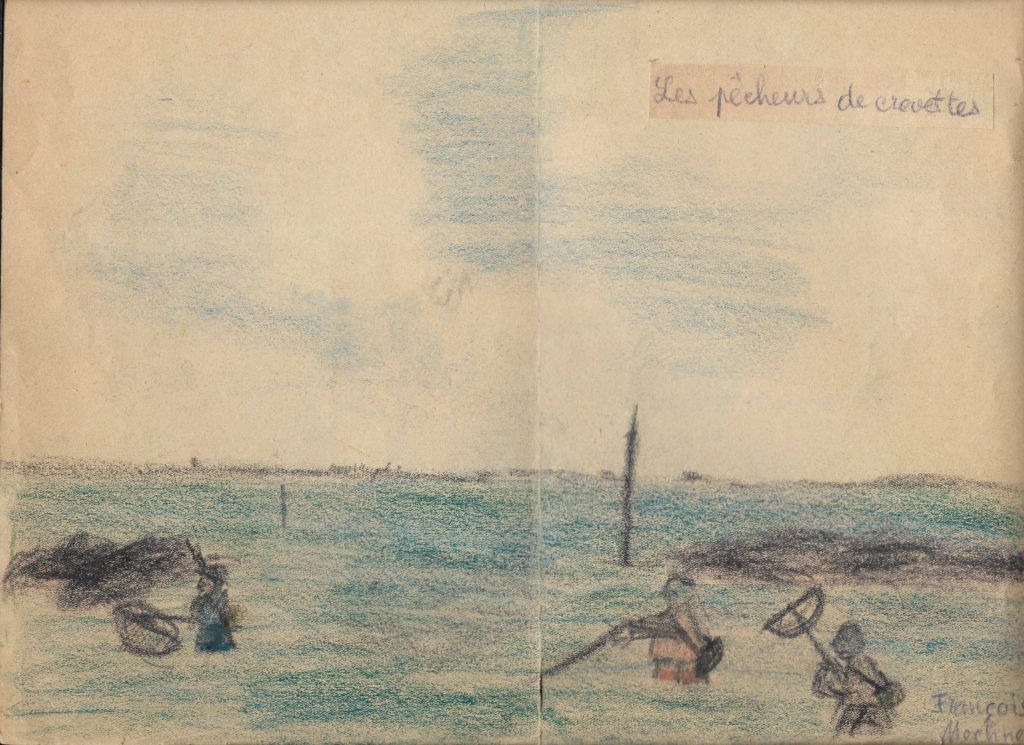

Mussels were plentiful on the jagged rocks that were exposed and accessible when the tide receded. M. Roi showed me how to harvest them and made them into delicious moules mariniere. He also taught me how to catch shrimp. We used special shrimp nets that looked like this:

The straight bar of the D would be pushed along the ocean bottom. The net was periodically lifted up and its shrimp contents emptied into a carrying pouch.

To prepare the shrimp, M. Roi threw them live into a big pot of seasoned boiling water. Most of the shrimp were of the tiny variety, but once in a while the batch also included some of the large crevettes roses (pink shrimp).

One rainy morning, M. Roi told me that he was promoting me to fisherman. “Come with me, François,” he said. “This weather and high tide are perfect for eels.”

Using worms as bait, I pulled up eels as fast as I could throw the fishing line back into the water from the top of the embankment. The eels were about twelve to eighteen inches long. After a few hours of fishing in the rain, I enjoyed coming back into the house to get dry and warm. It was also satisfying to me to know that I was contributing to our subsistence. The way M. Roi prepared the eels, they were delicious and had a chewy texture.

Chapter 64. Ouch!

About once a month, the low tide receded about one kilometer, exposing vast stretches of craggy rocks. When the tide was at its low point, the local fishermen would walk far out into the exposed ocean bed to catch stranded crabs, shrimp, mussels, and the big conger eels.

On one of those occasions, some fishermen took me along. We walked about one kilometer out from the shore. There I was able to watch them hunt conger eels, which grew to lengths of over a meter. The fisher¬men went after them with long, two pronged pitchforks that they poked into the deep crevices in which conger eels were left stranded when the tide receded. I couldn’t understand how the fishermen could spear them without actually seeing them, but they could. After a lot of poking, we would hear violent thrashing inside the crevice, and the fisherman would gleefully pull out the speared conger eel bleeding and writhing on the pitchfork. I found that gruesome.

As I wandered around exploring the strange and fascinating low tide landscape, I noticed an unusually high rock with a smooth diagonal slope that was beautifully lubricated with slimy algae. What a great slide this would make! I climbed to the top, sat down, put the palms of my hands down beside me to stabilize myself, and slid down into the water with great speed. Unfortunately, on the way down, a sharp piece of shell jutting out of the rock cut through the palm of my left hand.

I was bleeding profusely, and the ocean water was turning red. The fishermen made a tourniquet to stem the bleeding and made me hold my arm up high as they carried me back to shore. Lisa called a doctor. He sewed me up and instructed us to let the wound heal in the sun, with the bandages removed. So, I had to sit in the garden for hours every day with my palm turned to the sun.

I alleviated the boredom of sitting there by drawing scenes of the beach and ocean with my crayons. That was when I discovered that impressionistic techniques could be extended to drawing landscapes and seascapes. Starting back in Vienna, I had been working on ways to draw butterflies in flight, as they actually looked to the observer. I didn’t have a name for those techniques, but had seen them used in the water color illustrations of my animal books and in the paintings I saw standing on the sidewalk in Paris when we were moving into 18 rue de l’Atlas. By using those techniques I tried to convey the overall visual impression rather than the photographic reality. One of the drawings I made while sunning my hand showed the Île de Noirmoutier in the distance (See below), one showed shrimp fishermen at work, and a third showed the sluice.

Chapter 65. A Macabre Intrusion of the War

In La Bernerie we were untouched by the war except for one eerie incident. A British merchant ship had been sunk somewhere off the coast, and an oil slick washed ashore along with the bodies of British sailors, still wearing yellow raincoats and boots.

For days, I refused to go near the beach, or even look in its direction. I returned only after I had been assured that all signs of dead bodies had been removed. I was also upset when I later saw some of the local fishermen wearing yellow raincoats and boots. Such callousness, I thought.

But that incident had another fallout, one from which I did not mind benefiting. The oil slick tarred up the feathers of the local water fowl, mostly ducks, which then became easy prey for anyone inclined to hunt them. I couldn’t bring myself to do that, but others did, and it was wonderful to have a brief change from our steady fare of seafood.

Chapter 66. I Anger M. Roi

M. Roi always demanded great respect from everyone around him. One morning, as we arrived at his house for lunch, I was distracted by some goings-on and neglected to greet him. He became livid with rage, screamed at me, and summarily ordered me back to our cabin.

I was devastated. My daily activities had revolved around efforts to win M. Roi’s approval, and now I felt that I would never be able to redeem myself in his eyes. From that time on, I generally tried to avoid him.

After that incident I spent more time with the three Polish girls. They had a record player and a few American records, which they played over and over and which I loved. They also treasured their supply of English cigarettes, and taught me the great difference between the smell of English tobacco and other types. The English cigarettes definitely smelled milder.

I had an especially warm relationship with Hélene, the youngest of the three sisters, who was sixteen. She was pretty, vivacious, and had curly blondish hair. She always wanted to dress me, comb my hair, and generally mother me. On one occasion, when I expressed some modesty while she was bathing me, she assured me that she had seen little boys’ penises before. I didn’t consider this fact particularly relevant, nor did it change my feeling of modesty, but I decided not to make an issue of it. Although I liked Hélene and enjoyed listening to her sing the American songs she played on her record player, I didn’t want to be mothered by her. I wanted to be mothered only by Lisa, whose attentions I was now often missing.

Chapter 67. Good-Bye to La Bernerie

In mid-November of 1940, after about two months in La Bernerie, we heard that the Germans were approaching in their southward advance, occupying one town after another. So Lisa decided to make a break for it and try to get to the unoccupied zone, without Baer, I was happy to learn.

The last big event in La Bernerie before our departure was the grape harvest. For the occasion, our whole ménage went into town. By this time, our neighbors had become sufficiently aware of our presence in La Bernerie that there no longer seemed to be any point to trying to hide from them. Besides, we were planning to leave La Bernerie shortly anyway. So, I was permitted to participate in the harvest festivities.

All the grapes had been put into a giant vat, and the local donkey, which I had been petting, pulled the giant handle of the vise that squeezed the grape juice into barrels. At some point I was told that this poor, old, hard working donkey would be made into salami as soon as his current work stint was completed. It was painful for me to watch the loyal beast straining to fill barrel after barrel with grape juice for his future executioners.

There were some minor celebrations and group games followed by a festive “drink in,” the main point of which seemed to be to get drunk. I did, for the first time in my life, and had great fun.

We had spent a little over two months in La Bernerie, but saying good bye to it was easy for me indeed, as I had been quite unhappy there. Our eventual destination, Lisa explained, was Vichy—the capital of the unoccupied zone of France—where we would be safer from the Germans. Lisa also thought that Lucy Feingold (Raymond’s wife), now in Vichy, might be able to assist us because of her position at the Alliance Israelite.

ut getting to Vichy would be no simple matter. We first had to go to Paris, where Lisa would have to persuade the German authorities to give us a laisser passer—a sort of visa or travel permit.

Mme. Roi drove us to nearby Nantes to catch a train to Paris. In Nantes, she took us to an elegant second story restaurant for a good bye lunch. Lisa ordered oysters as an appetizer and I was shocked when told that oysters are eaten alive. In spite of her coaxing, I couldn’t bring myself to try one. For dessert I ordered a tarte aux cerises, my first one since Paris-Plage.

During dessert, Mme. Roi pressed a thousand-franc note into Lisa’s hand.

“Don’t tell Henri that I gave you this,” she said in an emotional voice.

At first, Lisa didn’t want to accept the money, but she finally did. I think she had to, as she had no money at all.